The God of Gods: A Canadian Play

by Carroll Aikins, edited and with an introduction by Kailin Wright

University of Ottawa Press, 2016

$29.95 / 9780776623276

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

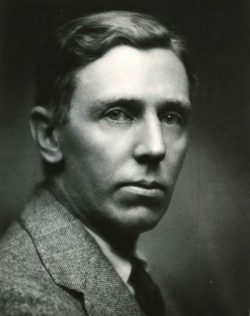

Although a remarkable piece of British Columbia’s theatre history played out not far from where I write and was the subject of a 1986 article by my former mentor and research partner at Thompson Rivers University, James Hoffman,[i] it took some stellar sleuthing by Ormsby Review editor Richard Mackie to shift Carroll Aikins’ The God of Gods: A Canadian Play from my peripheral to my central vision.

Although a remarkable piece of British Columbia’s theatre history played out not far from where I write and was the subject of a 1986 article by my former mentor and research partner at Thompson Rivers University, James Hoffman,[i] it took some stellar sleuthing by Ormsby Review editor Richard Mackie to shift Carroll Aikins’ The God of Gods: A Canadian Play from my peripheral to my central vision.

In the early 1920s, Naramata, B.C. was the site of a combined theatre and fruit-packing business founded by a central Canadian who (in 1908) had transplanted himself there for a health cure. In the few years that Home Theatre existed, Aikins, a cultural nationalist, trained Canadian actors in Canadian productions, earning it media recognition as this country’s first national theatre.

Before returning to Central Canada (where he would become artistic director of Toronto’s Hart House Theatre by the end of the decade) Aikins also wrote at least five plays. Editor Kailin Wright speculates, credibly, that The God of Gods was the sole Aikins play to be produced because it alone has an all-Indigenous cast of characters.

Wright’s comprehensive edition is part of The Canadian Literature collection, a series of 19th – mid 20th century literary texts previously out of print or unpublished. Wright’s scholarly introduction is extensive, insightful, and meticulously detailed, reading the play in the contexts of, for example, primitivism, modernism, and theosophy. The script is also complemented by explanatory and textual notes and primary material such as production shots, reproductions of playbills, reviews, and the like. Wright’s combination of popular and academic approaches sits well with this reviewer.

Written at Naramata in 1918 and set in an indeterminate time and place, The God of Gods is a love triangle/tragedy that pits wealth, power and pseudo-religion against art, beauty, and spirituality. Protagonist Suiva, who is physically beautiful, spiritually rich, and materially poor, is the object of the affections of both Malbo, the son of Chief Amburi, and Yellow Snake, a singer and poet.

Suiva initially handles the situation strategically, issuing each suitor a challenge that requires them to exercise faculties they rarely use. While Yellow Snake cannot literally succeed in his challenge, he does succeed imaginatively. When the gluttonous and physically and mentally lazy Malbo quickly fails in his challenge, Suiva summarily dismisses him and declares her love for Yellow Snake.

However, the lovers’ joy is short lived. Malbo, in league with the outgoing priestess of the God of Gods, Waning Moon, and Suiva’s mother, Kotowi (who, Suiva learns later, has agreed to sell her daughter to Malbo), plots to make Suiva Waning Moon’s replacement. By the end of Act 1, Malbo has abducted Suiva. As the custom is that the virgin priestess must be gated, and the Chief’s son is the only male allowed inside the gate, Malbo seems to be assuring his victory in this contest.

Act 11 begins with Suiva not only resigned to her fate, but dutiful in preparation for her new role. She conveys a message to Yellow Snake, who waits at the gate with a bow and arrow: although she will love him forever, he must leave and never return.

Waning Moon proves a most instructive coach on the roles and responsibilities of the priestess position. While the priestess must tend Malbo’s fire and not love or be loved by men, in her primary mission to deliver God’s message to the people (who must obey or die) she has the power to interpret what God might mean in light of what the people might want to hear. The spiritual waters are becoming murky here.

There is more cause for scepticism as the two women prepare for Suiva’s induction ceremony, yet Suiva remains steadfast in her commitment to duty. Yellow Snake enters unseen, but eventually makes himself known — declaring his love and challenging the power of “the stone god.” He also informs Suiva of her mother’s betrayal, begs her not to take vows, and exits.

But Suiva’s faith and the powers-that-be prevail: the ceremony proceeds, with Amburi, Malbo, and a throng of worshippers present, and Waning Moon dominating the proceedings. At the point when Suiva vows to renounce all men and serve the God of Gods, Yellow Snake (again a secret witness) can restrain himself no longer, and Act 11 ends with Amburi (unbeknownst to Suiva) ordering Malbo to kill Yellow Snake.

Act 111 opens with Waning Moon training Suiva in fire tending. Idealist Suiva believes she will die if she allows the fire to extinguish. Pragmatist Waning Moon admits to having been too drunk, often, to worry about such things, and proceeds to disavow her protégé of many of her religious beliefs, to the point that it is clear that the priestess is the God of Gods in disguise: i.e., the God of Gods does not exist. Bereft and regretful, Suiva, who has also had to fend off Malbo’s sexual advances, finally faces the reality that the political, religious, and even familial systems to which she has been so faithful are hollow.

When Amburi learns that Malbo has killed Yellow Snake in a cowardly fashion (striking him unawares from behind) his rage overtakes any semblance of reason. Taking direction from Waning Moon, he orders his son to wear women’s clothing “for the passing of one moon.”

The Chief then orders that Yellow Snake’s body be shown to Suiva: if it appears she loved him, she must die to appease the God of Gods, who will otherwise punish the entire population.

After being told her true love was killed as an enemy of her people, Suiva carries on with her duty as priestess to perform the rites on his body. Immediately afterward, however, she denies he is their enemy; instead, she confesses her love and takes her life into her own hands when she forsakes the God of Gods and declares Yellow Snake as God.

*

Of primary contemporary interest in God of Gods is the depiction by a white settler of an Indigenous culture. Wright notes that the play’s setting may well have been inspired by the Syilx (Okanagan) people. She bases her understanding on the Okanagan First Peoples project and cites, for example, the Syilx Nation’s beliefs that memory is preserved in their material and spiritual culture. Rocks, the earth, and all that inhabits it are a singular entity, and life is created and sustained by the coming together of all elements and inhabitants. However, Wright also acknowledges the play’s “faux-native dialogue and reductive character portrayals.” As for the lack of geographical specificity, she perceives it as a feature of the play’s modernism, rather than a failure on the part of Aikins to achieve realism.

In this vein, the production history and reviewer responses to The God of Gods are worth mentioning. The play’s premier at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1919 was followed by a Hart House production in the 1921-22 season and, almost a decade later, a run at London’s Everyman Theatre. Reviewers variously read the play as realist and modernist, with Canadian reviewers (whether of the Canadian or British productions) tending to be more questioning of the “authenticity” of both the Canadian and Aboriginal setting, and reviewers of the initial production most accepting. Wright is thoroughgoing in her reconstruction and examination of each production.

Theatre and cultural historians would find this edition worth digging into, and its comprehensiveness makes it tailor-made for the classroom, particularly a graduate course in Canadian or British Columbian theatre or literature. Those with a focus on place-based or rural studies, comparative audience reception, depiction of Indigenous cultures by settlers, and issues of cultural appropriation (among others), will also find much food for thought here.

My belated immersion into Carroll Aikins’ enterprise in a tiny rural community has prompted me to reflect on the important role the rural British Columbia interior has played in developing home-grown theatre. B.C. was, as James Hoffman remarks, “the stagiest of provinces.” I think of visions similar to that of Aikins – but later, in the height of the Canadian cultural nationalist movement that began in the 1960s.

Of course, Summerland, where George Ryga based himself for many years, comes to mind. Alan Twigg’s BC Booklook entry on Ryga quotes John Juliani: “More than any other writer, George Ryga was responsible for first bringing the contemporary age to the Canadian stage.” Moving north just a bit, we find Armstrong’s Caravan Farm Theatre which, its website reminds us, in 2018 celebrated forty years of reflecting “the contemporary rural British Columbian experience” — proudly, without an actual theatre building.

Important and unusual stages can emanate from small, unlikely places.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is an Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University specializing in Canadian literature. Recent courses have included Modern Canadian Drama and The Environment in Canadian Literature. She has published articles on theatre, playwrights, and small cities in British Columbia including Playing the Pacific Province (2001, co-edited with James Hoffman), Theatre in British Columbia (2006), and she has also co-edited (with W.F. Garrett-Petts and James Hoffman) Whose Culture Is It, Anyway? Community Engagement in Small Cities (New Star Books, Limited, 2014). Her latest academic publication is about a wonderful third-age learning organization, The Kamloops Adult Learners Society, in No Straight Lines: Local Leadership and the Path from Government to Government in Small Cities, edited by Terry Kading (University of Calgary Press, 2018), reviewed in The Ormsby Review #473 (January 27, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnote:

[i] See James Hoffman, “Carroll Aikins and the Home Theatre,” Theatre Research in Canada 7: 1 (Spring 1986): https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/TRIC/article/view/7407

*

[BCBW 2019]

by Carroll Aikins, edited and with an introduction by Kailin Wright

University of Ottawa Press, 2016

$29.95 / 9780776623276

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

Although a remarkable piece of British Columbia’s theatre history played out not far from where I write and was the subject of a 1986 article by my former mentor and research partner at Thompson Rivers University, James Hoffman,[i] it took some stellar sleuthing by Ormsby Review editor Richard Mackie to shift Carroll Aikins’ The God of Gods: A Canadian Play from my peripheral to my central vision.

Although a remarkable piece of British Columbia’s theatre history played out not far from where I write and was the subject of a 1986 article by my former mentor and research partner at Thompson Rivers University, James Hoffman,[i] it took some stellar sleuthing by Ormsby Review editor Richard Mackie to shift Carroll Aikins’ The God of Gods: A Canadian Play from my peripheral to my central vision.In the early 1920s, Naramata, B.C. was the site of a combined theatre and fruit-packing business founded by a central Canadian who (in 1908) had transplanted himself there for a health cure. In the few years that Home Theatre existed, Aikins, a cultural nationalist, trained Canadian actors in Canadian productions, earning it media recognition as this country’s first national theatre.

Before returning to Central Canada (where he would become artistic director of Toronto’s Hart House Theatre by the end of the decade) Aikins also wrote at least five plays. Editor Kailin Wright speculates, credibly, that The God of Gods was the sole Aikins play to be produced because it alone has an all-Indigenous cast of characters.

Wright’s comprehensive edition is part of The Canadian Literature collection, a series of 19th – mid 20th century literary texts previously out of print or unpublished. Wright’s scholarly introduction is extensive, insightful, and meticulously detailed, reading the play in the contexts of, for example, primitivism, modernism, and theosophy. The script is also complemented by explanatory and textual notes and primary material such as production shots, reproductions of playbills, reviews, and the like. Wright’s combination of popular and academic approaches sits well with this reviewer.

Written at Naramata in 1918 and set in an indeterminate time and place, The God of Gods is a love triangle/tragedy that pits wealth, power and pseudo-religion against art, beauty, and spirituality. Protagonist Suiva, who is physically beautiful, spiritually rich, and materially poor, is the object of the affections of both Malbo, the son of Chief Amburi, and Yellow Snake, a singer and poet.

Suiva initially handles the situation strategically, issuing each suitor a challenge that requires them to exercise faculties they rarely use. While Yellow Snake cannot literally succeed in his challenge, he does succeed imaginatively. When the gluttonous and physically and mentally lazy Malbo quickly fails in his challenge, Suiva summarily dismisses him and declares her love for Yellow Snake.

However, the lovers’ joy is short lived. Malbo, in league with the outgoing priestess of the God of Gods, Waning Moon, and Suiva’s mother, Kotowi (who, Suiva learns later, has agreed to sell her daughter to Malbo), plots to make Suiva Waning Moon’s replacement. By the end of Act 1, Malbo has abducted Suiva. As the custom is that the virgin priestess must be gated, and the Chief’s son is the only male allowed inside the gate, Malbo seems to be assuring his victory in this contest.

Act 11 begins with Suiva not only resigned to her fate, but dutiful in preparation for her new role. She conveys a message to Yellow Snake, who waits at the gate with a bow and arrow: although she will love him forever, he must leave and never return.

Waning Moon proves a most instructive coach on the roles and responsibilities of the priestess position. While the priestess must tend Malbo’s fire and not love or be loved by men, in her primary mission to deliver God’s message to the people (who must obey or die) she has the power to interpret what God might mean in light of what the people might want to hear. The spiritual waters are becoming murky here.

There is more cause for scepticism as the two women prepare for Suiva’s induction ceremony, yet Suiva remains steadfast in her commitment to duty. Yellow Snake enters unseen, but eventually makes himself known — declaring his love and challenging the power of “the stone god.” He also informs Suiva of her mother’s betrayal, begs her not to take vows, and exits.

But Suiva’s faith and the powers-that-be prevail: the ceremony proceeds, with Amburi, Malbo, and a throng of worshippers present, and Waning Moon dominating the proceedings. At the point when Suiva vows to renounce all men and serve the God of Gods, Yellow Snake (again a secret witness) can restrain himself no longer, and Act 11 ends with Amburi (unbeknownst to Suiva) ordering Malbo to kill Yellow Snake.

Act 111 opens with Waning Moon training Suiva in fire tending. Idealist Suiva believes she will die if she allows the fire to extinguish. Pragmatist Waning Moon admits to having been too drunk, often, to worry about such things, and proceeds to disavow her protégé of many of her religious beliefs, to the point that it is clear that the priestess is the God of Gods in disguise: i.e., the God of Gods does not exist. Bereft and regretful, Suiva, who has also had to fend off Malbo’s sexual advances, finally faces the reality that the political, religious, and even familial systems to which she has been so faithful are hollow.

When Amburi learns that Malbo has killed Yellow Snake in a cowardly fashion (striking him unawares from behind) his rage overtakes any semblance of reason. Taking direction from Waning Moon, he orders his son to wear women’s clothing “for the passing of one moon.”

The Chief then orders that Yellow Snake’s body be shown to Suiva: if it appears she loved him, she must die to appease the God of Gods, who will otherwise punish the entire population.

After being told her true love was killed as an enemy of her people, Suiva carries on with her duty as priestess to perform the rites on his body. Immediately afterward, however, she denies he is their enemy; instead, she confesses her love and takes her life into her own hands when she forsakes the God of Gods and declares Yellow Snake as God.

*

Pillar Rock near Falkland, the boundary marker between Syilx (Okanagan) and Secwépemc (Shuswap) territory

Of primary contemporary interest in God of Gods is the depiction by a white settler of an Indigenous culture. Wright notes that the play’s setting may well have been inspired by the Syilx (Okanagan) people. She bases her understanding on the Okanagan First Peoples project and cites, for example, the Syilx Nation’s beliefs that memory is preserved in their material and spiritual culture. Rocks, the earth, and all that inhabits it are a singular entity, and life is created and sustained by the coming together of all elements and inhabitants. However, Wright also acknowledges the play’s “faux-native dialogue and reductive character portrayals.” As for the lack of geographical specificity, she perceives it as a feature of the play’s modernism, rather than a failure on the part of Aikins to achieve realism.

In this vein, the production history and reviewer responses to The God of Gods are worth mentioning. The play’s premier at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1919 was followed by a Hart House production in the 1921-22 season and, almost a decade later, a run at London’s Everyman Theatre. Reviewers variously read the play as realist and modernist, with Canadian reviewers (whether of the Canadian or British productions) tending to be more questioning of the “authenticity” of both the Canadian and Aboriginal setting, and reviewers of the initial production most accepting. Wright is thoroughgoing in her reconstruction and examination of each production.

Theatre and cultural historians would find this edition worth digging into, and its comprehensiveness makes it tailor-made for the classroom, particularly a graduate course in Canadian or British Columbian theatre or literature. Those with a focus on place-based or rural studies, comparative audience reception, depiction of Indigenous cultures by settlers, and issues of cultural appropriation (among others), will also find much food for thought here.

My belated immersion into Carroll Aikins’ enterprise in a tiny rural community has prompted me to reflect on the important role the rural British Columbia interior has played in developing home-grown theatre. B.C. was, as James Hoffman remarks, “the stagiest of provinces.” I think of visions similar to that of Aikins – but later, in the height of the Canadian cultural nationalist movement that began in the 1960s.

Of course, Summerland, where George Ryga based himself for many years, comes to mind. Alan Twigg’s BC Booklook entry on Ryga quotes John Juliani: “More than any other writer, George Ryga was responsible for first bringing the contemporary age to the Canadian stage.” Moving north just a bit, we find Armstrong’s Caravan Farm Theatre which, its website reminds us, in 2018 celebrated forty years of reflecting “the contemporary rural British Columbian experience” — proudly, without an actual theatre building.

Important and unusual stages can emanate from small, unlikely places.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is an Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University specializing in Canadian literature. Recent courses have included Modern Canadian Drama and The Environment in Canadian Literature. She has published articles on theatre, playwrights, and small cities in British Columbia including Playing the Pacific Province (2001, co-edited with James Hoffman), Theatre in British Columbia (2006), and she has also co-edited (with W.F. Garrett-Petts and James Hoffman) Whose Culture Is It, Anyway? Community Engagement in Small Cities (New Star Books, Limited, 2014). Her latest academic publication is about a wonderful third-age learning organization, The Kamloops Adult Learners Society, in No Straight Lines: Local Leadership and the Path from Government to Government in Small Cities, edited by Terry Kading (University of Calgary Press, 2018), reviewed in The Ormsby Review #473 (January 27, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnote:

[i] See James Hoffman, “Carroll Aikins and the Home Theatre,” Theatre Research in Canada 7: 1 (Spring 1986): https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/TRIC/article/view/7407

*

Kailin Wright (left) with fellow series editors, Laurie Kruk (Double Voicing the Canadian Short Story) and Miguel Mota, Malcolm Lowry, The 1940 Under the Volcano: A Critical Edition, all University of Ottawa Press

[BCBW 2019]

Home

Home