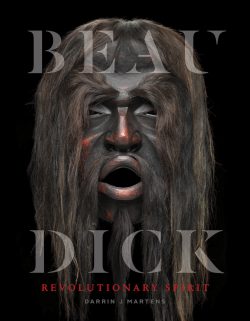

Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit

edited by Darren J. Martens in collaboration with the Audain Art Museum

Vancouver: Figure 1, 2018

$40 / 9781773270401

Reviewed by Alan L. Hoover

*

Chief Beau Dick (Walas Gwa’yam) (1955-2017) was a much-honoured artist and activist in the Kwakwaka’wakw community, the wider Indigenous and non-Indigenous arts community of British Columbia, and the academy. His passing at the too young age of 61 has been mourned by members from all these spheres.

Born in Alert Bay and raised in the small community of Kingcome, and then in Vancouver, Dick worked with his father, Ben Dick, and later studied under senior artists Doug Cranmer and Henry Hunt. His work was first collected by major B.C. museums in the 1970s and 1980s, when he was in his twenties. From the start of his career he was recognized as having a talent to carve in many tribal styles, not just in the style of his own Kwakwaka’wakw tradition. Beau Dick’s work is in many private and institutional collections including the Canadian Museum of History, the Royal BC Museum, the UBC Museum of Anthropology, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Heard Museum (Phoenix), and the Burke Museum (Seattle).

Dick was awarded a 2011 VIVA Award, presented annually by the Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts in recognition of B.C. artists who demonstrate exceptional creative ability and commitment. In 2013 he was appointed as the Artist in Residence at the UBC Department of Art History. Initially the residency was for a three-month term but ended up being extended to six years in recognition of the great value of the supportive mentorship he generously gave to the many students he met and worked with.

Like many Kwakwaka’wakw artists, Dick produced work that was used in the continuing dramatic ceremonial life of his people’s communities. However, Dick then chose to apply his knowledge of Kwakwaka’wakw cultural traditions out into the world of politics and social advocacy. In 2013, supported by his family, community, and the Idle No More movement, he initiated a trek from Quatsino on northern Vancouver Island to the Legislature in Victoria.

He and his companions ceremonially broke a copper, an act fraught with traditional meaning and an expression of anguish to shame the government of B.C. for its inaction in addressing longstanding Indigenous and environmental grievances and injustices.

Again, in 2014 Haida leader Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw) and Beau Dick led a group of protesters across Canada to Ottawa, where they broke Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw coppers to draw attention to the Harper government’s broken relations with Indigenous peoples. This activism is recorded in the 2018 documentary movie Maker of Monsters: The Extraordinary Life of Beau Dick, written and directed by Natalie Boll and LaTiesha Fazakas.

Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit is a beautifully illustrated book, a photographic record of a retrospective of Beau Dick’s work exhibited at Whistler’s Audain Art Museum between March and June 2018, featuring 89 pieces of Dick’s work. This book includes 44 of Dick’s wonderfully carved masks, two dramatic articulated puppets, a fine raven rattle, two dancing headdresses, a painted leather apron, and ten silkscreen prints. A number of pieces illustrating Beau Dick’s mastery of different Northwest Coast art styles appear in the book, including a large model totem pole in the style of Haida artist Charles Edenshaw, a Tsimshian style headdress frontlet, and two Nuxalk-style Thunder masks.

In addition to the colour photographs of objects and stills of the artist, exhibit curator and book editor Darrin Martens discusses Dick’s work and career in a 13-page essay divided into headings “The Man,” “The Mentor,” “The Activist,” “The Artist,” and “The Legacy.”

Martens emphasizes the differences between Dick’s work produced for the art market and for potlatches. “Each piece is carefully considered,” he writes, “meticulously executed and presented for maximum effect, [which is] a very different approach from that used in his work for potlatch ceremonies.”

And it was here that I wanted a bit more curatorial input. Martens introduces Dick’s appealing phrase “potlatch perfect” to describe his pieces intended for use in the potlatch. Martens explains that this was “not meant as a term of derision or an insult; rather, it references a series of works (often masks that are not market ready) created for use within a potlatch celebration.” However, none of the objects illustrated in Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit are identified as having been made specifically for potlatch use, so the reader cannot see the differences that Martens references.

Martens balances these two aspects of Beau Dick’s oeuvre, items for potlatch use and for sale, stating that while he mentored others to recognize that creating work for the market is both meaningful and a way “to create new work, feed one’s family, and help the Community, … [Dick’s] proficiency in creating unique and distinctive objects and donating them to potlatches is unmatched.”

Nor does Martens discuss the attraction that both museums and collectors have in obtaining pieces that were in fact used in potlatches and thus carry the cachet of “authenticity.”

The book’s other textual piece is a Letter to Beau Dick written by Tahltan Nation writer and academic Peter Morin some time after the artist passed away. Morin then burned the letter, but it is reproduced here in its original seven-page hand-printed form. In it, Morin discusses the role of the Indigenous artist and how Beau Dick was, and remains, so important to the practice of west coast art.

An unusual and poignant touch is the inclusion of a poem about the artist written by his daughter Linnea Dick, who also contributed as co-curator of the exhibition that the book memorializes.

If you are unfamiliar with Beau Dick’s work or simply want a record of it, Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit will serve you well.

“My conscience tells me we have to fight back." -- Beau Dick

Beau Dick: Devoured by Consumerism (Figure.1 2019), edited by LaTiesha Fazaka, with writing by John Cussans and Candice Hopkins, has been published in collaboration with Fazakas Gallery in conjunction with an exhibition that debuted at the White Columns gallery in New York City, March 16 to May 4, 2019.

In an interview done by Robin Laurence for Georgia Straight (June 2019), Fazaka recalled meeting the artist eighteen years before and thinking, "Does nobody realize that this guy is van Gogh, this guy is Duchamp, this guy is groundbreaking?... Why isn’t Beau Dick’s name on everybody’s lips? He is here in Canada and he is so amazing!"

As young man whose Kwakwaka’wakw name was Walas Gwa’yam (“Big Whale”), Beau Dick, born in Alert Bay but raised in remote Kingcome, came to the big city and partied hard with cocaine. Eventually he kicked the habit, healing himself with a return to Alert Bay and traditional spirituality.

Along the way he developed his own approaches to carving after learning his craft from artists that included his grandfather James Dick, his father Benjamin Dick, Henry Hunt, Doug Cranmer, Robert Davidson, Tony Hunt and Bill Reid.

As a high-ranking member of Hamat’sa--a secret Kwakwaka’wakw society that focusses on the story of a man-eating spirit--Beau Dick (1955–2017) increasingly danced in and led elaborate ceremonies that enacted Kwakwaka’wakw cosmology.

First Nations art critic Julian Brave NoiseCat, a member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen and descendant of the Lil’Wat Nation of Mount Currie, has brilliantly responded to the travelling exhibit while summarizing Dick's consistent protests against consumerism as a form of non-violent, spiritual warfare:

"In 2008, Dick became the first artist in 50 years to return a set of Atlakima masks, to be danced and burned in ceremony at his home community of Alert Bay—an act of defiance against the economic and ethnographic imperative to collect and preserve. He repeated this cycle in 2012, to dance and burn tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of art back in Kwakwaka’wakw territory. In 2013, during the Idle No More movement, Dick made a copper crest representative of a hereditary chief’s title and wealth. With two of his daughters, Linnea and Geraldine, as well as members of his nation and an entourage of 3,000 activists, he marched the copper to the steps of the provincial capital in Victoria, where he smashed it in protest. In 2014, Dick led a similar pilgrimage to Ottawa alongside Guujaaw Edenshaw, a Haida artist and leader. On Parliament Hill, Dick, Edenshaw and First Nations leaders broke the copper to shame the government for its treatment of Indigenous peoples...”

Dick’s activism was recorded in a 2018 documentary movie Maker of Monsters: The Extraordinary Life of Beau Dick, written and directed by Natalie Boll and LaTiesha Fazakas.

Artist, heal, thyself. Anti-capitalism led Beau Dick to express links between the ravenous Hamat'sa spirit and rampant consumerism. His artistry and his ceremonial actions were both attempts to come to terms with voracious appetites.

"Dick was one of the best carvers in the world,” according to Julian Brave NoiseCat, “but the real power of his work lay in the possibility that he might peel his art off the wall, dance it, burn it, smash it or otherwise assert its Kwakwaka’wakw spiritual value above and beyond its exchange value."

ILMBC2

edited by Darren J. Martens in collaboration with the Audain Art Museum

Vancouver: Figure 1, 2018

$40 / 9781773270401

Reviewed by Alan L. Hoover

*

Chief Beau Dick (Walas Gwa’yam) (1955-2017) was a much-honoured artist and activist in the Kwakwaka’wakw community, the wider Indigenous and non-Indigenous arts community of British Columbia, and the academy. His passing at the too young age of 61 has been mourned by members from all these spheres.

Born in Alert Bay and raised in the small community of Kingcome, and then in Vancouver, Dick worked with his father, Ben Dick, and later studied under senior artists Doug Cranmer and Henry Hunt. His work was first collected by major B.C. museums in the 1970s and 1980s, when he was in his twenties. From the start of his career he was recognized as having a talent to carve in many tribal styles, not just in the style of his own Kwakwaka’wakw tradition. Beau Dick’s work is in many private and institutional collections including the Canadian Museum of History, the Royal BC Museum, the UBC Museum of Anthropology, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Heard Museum (Phoenix), and the Burke Museum (Seattle).

Dick was awarded a 2011 VIVA Award, presented annually by the Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts in recognition of B.C. artists who demonstrate exceptional creative ability and commitment. In 2013 he was appointed as the Artist in Residence at the UBC Department of Art History. Initially the residency was for a three-month term but ended up being extended to six years in recognition of the great value of the supportive mentorship he generously gave to the many students he met and worked with.

Like many Kwakwaka’wakw artists, Dick produced work that was used in the continuing dramatic ceremonial life of his people’s communities. However, Dick then chose to apply his knowledge of Kwakwaka’wakw cultural traditions out into the world of politics and social advocacy. In 2013, supported by his family, community, and the Idle No More movement, he initiated a trek from Quatsino on northern Vancouver Island to the Legislature in Victoria.

He and his companions ceremonially broke a copper, an act fraught with traditional meaning and an expression of anguish to shame the government of B.C. for its inaction in addressing longstanding Indigenous and environmental grievances and injustices.

Again, in 2014 Haida leader Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw) and Beau Dick led a group of protesters across Canada to Ottawa, where they broke Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw coppers to draw attention to the Harper government’s broken relations with Indigenous peoples. This activism is recorded in the 2018 documentary movie Maker of Monsters: The Extraordinary Life of Beau Dick, written and directed by Natalie Boll and LaTiesha Fazakas.

Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit is a beautifully illustrated book, a photographic record of a retrospective of Beau Dick’s work exhibited at Whistler’s Audain Art Museum between March and June 2018, featuring 89 pieces of Dick’s work. This book includes 44 of Dick’s wonderfully carved masks, two dramatic articulated puppets, a fine raven rattle, two dancing headdresses, a painted leather apron, and ten silkscreen prints. A number of pieces illustrating Beau Dick’s mastery of different Northwest Coast art styles appear in the book, including a large model totem pole in the style of Haida artist Charles Edenshaw, a Tsimshian style headdress frontlet, and two Nuxalk-style Thunder masks.

In addition to the colour photographs of objects and stills of the artist, exhibit curator and book editor Darrin Martens discusses Dick’s work and career in a 13-page essay divided into headings “The Man,” “The Mentor,” “The Activist,” “The Artist,” and “The Legacy.”

Martens emphasizes the differences between Dick’s work produced for the art market and for potlatches. “Each piece is carefully considered,” he writes, “meticulously executed and presented for maximum effect, [which is] a very different approach from that used in his work for potlatch ceremonies.”

And it was here that I wanted a bit more curatorial input. Martens introduces Dick’s appealing phrase “potlatch perfect” to describe his pieces intended for use in the potlatch. Martens explains that this was “not meant as a term of derision or an insult; rather, it references a series of works (often masks that are not market ready) created for use within a potlatch celebration.” However, none of the objects illustrated in Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit are identified as having been made specifically for potlatch use, so the reader cannot see the differences that Martens references.

Martens balances these two aspects of Beau Dick’s oeuvre, items for potlatch use and for sale, stating that while he mentored others to recognize that creating work for the market is both meaningful and a way “to create new work, feed one’s family, and help the Community, … [Dick’s] proficiency in creating unique and distinctive objects and donating them to potlatches is unmatched.”

Nor does Martens discuss the attraction that both museums and collectors have in obtaining pieces that were in fact used in potlatches and thus carry the cachet of “authenticity.”

The book’s other textual piece is a Letter to Beau Dick written by Tahltan Nation writer and academic Peter Morin some time after the artist passed away. Morin then burned the letter, but it is reproduced here in its original seven-page hand-printed form. In it, Morin discusses the role of the Indigenous artist and how Beau Dick was, and remains, so important to the practice of west coast art.

An unusual and poignant touch is the inclusion of a poem about the artist written by his daughter Linnea Dick, who also contributed as co-curator of the exhibition that the book memorializes.

If you are unfamiliar with Beau Dick’s work or simply want a record of it, Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit will serve you well.

The spiritual warfare of Beau Dick

“My conscience tells me we have to fight back." -- Beau Dick

Beau Dick: Devoured by Consumerism (Figure.1 2019), edited by LaTiesha Fazaka, with writing by John Cussans and Candice Hopkins, has been published in collaboration with Fazakas Gallery in conjunction with an exhibition that debuted at the White Columns gallery in New York City, March 16 to May 4, 2019.

In an interview done by Robin Laurence for Georgia Straight (June 2019), Fazaka recalled meeting the artist eighteen years before and thinking, "Does nobody realize that this guy is van Gogh, this guy is Duchamp, this guy is groundbreaking?... Why isn’t Beau Dick’s name on everybody’s lips? He is here in Canada and he is so amazing!"

As young man whose Kwakwaka’wakw name was Walas Gwa’yam (“Big Whale”), Beau Dick, born in Alert Bay but raised in remote Kingcome, came to the big city and partied hard with cocaine. Eventually he kicked the habit, healing himself with a return to Alert Bay and traditional spirituality.

Along the way he developed his own approaches to carving after learning his craft from artists that included his grandfather James Dick, his father Benjamin Dick, Henry Hunt, Doug Cranmer, Robert Davidson, Tony Hunt and Bill Reid.

As a high-ranking member of Hamat’sa--a secret Kwakwaka’wakw society that focusses on the story of a man-eating spirit--Beau Dick (1955–2017) increasingly danced in and led elaborate ceremonies that enacted Kwakwaka’wakw cosmology.

First Nations art critic Julian Brave NoiseCat, a member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen and descendant of the Lil’Wat Nation of Mount Currie, has brilliantly responded to the travelling exhibit while summarizing Dick's consistent protests against consumerism as a form of non-violent, spiritual warfare:

"In 2008, Dick became the first artist in 50 years to return a set of Atlakima masks, to be danced and burned in ceremony at his home community of Alert Bay—an act of defiance against the economic and ethnographic imperative to collect and preserve. He repeated this cycle in 2012, to dance and burn tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of art back in Kwakwaka’wakw territory. In 2013, during the Idle No More movement, Dick made a copper crest representative of a hereditary chief’s title and wealth. With two of his daughters, Linnea and Geraldine, as well as members of his nation and an entourage of 3,000 activists, he marched the copper to the steps of the provincial capital in Victoria, where he smashed it in protest. In 2014, Dick led a similar pilgrimage to Ottawa alongside Guujaaw Edenshaw, a Haida artist and leader. On Parliament Hill, Dick, Edenshaw and First Nations leaders broke the copper to shame the government for its treatment of Indigenous peoples...”

Dick’s activism was recorded in a 2018 documentary movie Maker of Monsters: The Extraordinary Life of Beau Dick, written and directed by Natalie Boll and LaTiesha Fazakas.

Artist, heal, thyself. Anti-capitalism led Beau Dick to express links between the ravenous Hamat'sa spirit and rampant consumerism. His artistry and his ceremonial actions were both attempts to come to terms with voracious appetites.

"Dick was one of the best carvers in the world,” according to Julian Brave NoiseCat, “but the real power of his work lay in the possibility that he might peel his art off the wall, dance it, burn it, smash it or otherwise assert its Kwakwaka’wakw spiritual value above and beyond its exchange value."

ILMBC2

Home

Home