QUICK REFERENCE ENTRY:

If geography were an Olympic event, they'd accuse Derek Hayes of being on steroids. During the first decade of the new millennium, Hayes compiled, designed and wrote ten atlases and illustrated histories, starting with his self-published Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (1999), winner of the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award. Since that debut, Hayes has won many awards for tracing the exploration and settlement patterns of areas throughout Canada and the U.S.

These were followed by British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012), winner of three major awards: the inaugural Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize, the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize to recognize the author of the book that contributes most to the enjoyment and understanding of British Columbia, and the Lieutenant Governor's Award for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation. It was also shortlisted for the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award presented to the originating publisher and author(s) of the best book in terms of public appeal, initiative, design, production and content.

The first Hayes atlas was followed by Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (2001) and First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition across North America, and the Opening of the Continent (2001). With 370 maps charting the growth of Vancouver and its environs, Hayes' sixth large format atlas, and his eighth book, Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (2005), traces the region's development from the days when the village of Granville, with 30 buildings, was divided into lots in 1882 for a city to be called Liverpool. Hayes received the Lieutenant Governor's Medal for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation.

British Columbia was brought into the Canadian Confederation in 1871 in exchange for the promise of a transcontinental line to the West Coast. When the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1886, it bolstered economic development in the province, created the city of Vancouver and spurred others to build competing lines. In his prolifically illustrated Iron Road West (Harbour $44.95) Derek Hayes charts the development of the province through its competitive railway lines and he explores the emergence of the modern freight railway in British Columbia, including fully automated and computerized trains. 978-1-550178388

"I collected stamps as a child," Hayes explains, "and I wanted to know where they all came from, hence out came the atlas. Then I got into geography academically, then city planning. I like to think that if a picture is worth a thousand words, a map must be worth ten thousand. Having said that, I would emphasize I try to write history using maps as the primary illustration. This has a wider audience than if I only wrote books about maps."

FULL ENTRY:

Born in England, Derek Hayes came to UBC to undertake graduate work at the Geography department in 1969, having trained as a geographer at the University of Hull in England. His interest in botanical geography led him to import hobby greenhouses. A greenhouse contact in England then suggested he become the Canadian distributor for a series of gardening books. At first, the gardening titles by experts sold poorly. Then they were spotted at the PNE garden show by an avid B.C. gardener, Bill Vander Zalm, who encouraged the Art Knapp outlets throughout B.C. to carry Hayes' titles. Based in Delta, Cavendish Books subsequently produced more than 100 of its own mainly gardening-related books. This publishing success led Hayes to finally indulge his passion for maps.

In 1999 Hayes published his Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Cavendish). This first atlas received the Bill Duthie Booksellers Choice Award in 2000. "Quite frankly I had no idea that anybody in B.C other than myself was interested in maps," said Hayes, upon receiving the prize. "Luckily there were quite a few! The book contains lots of speculative maps about British Columbia because British Columbia is one of the last places in the world, other than the poles, to be put on the map of the world. Cartographers didn't like to have blanks on their maps. If they didn't know what was out there, they made it up. As a result there are some bizarre maps of what is now British Columbia. On one there is a great sea of the west that goes as far as Kansas. On another a Northwest Passage takes off somewhere near Prince Rupert and goes to Hudson's Bay. It's wild and it's woolly."

Hayes' Historical Atlas of Canada received the 2003 Lela Common Award for Canadian History from the Canadian Authors Association (and a revised edition was published in 2015). It was preceded by a study of Alexander Mackenzie and the Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (Douglas & McIntyre). "I've been collecting maps for 30 years," said Hayes, who says he spent more than $20,000 on reproduction fees. "The Russian ones were particularly difficult to track. It's been like detective work." The North Pacific atlas provides 235 maps that pertain directly to the territory now known as B.C. and 320 maps in all. Included are the voyages of Vitus Bering, the first map of the entire southern interior of B.C. made by Archibald McDonald in 1827, maps from the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1841, military spy maps of 1845 and 1846, American railroad surveys, British-American Boundary Commission maps, gold rush maps and maps for the purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867.

Hayes' British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012) was shortlisted for the inaugural Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize and the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize to recognize the author(s) of the book that contributes most to the enjoyment and understanding of British Columbia. It was also shortlisted for the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award presented to the originating publisher and author(s) of the best book in terms of public appeal, initiative, design, production and content.

As an historian who uses maps as an adjunct to his work, Hayes has also produced an illustrated history of Canada, to be followed by a similar work for the United States. He is involved in his own books as a designer, and has won three Alcuin Awards for his work as a packager of his own materials. With 370 maps charting the growth of Vancouver and its environs, Derek Hayes' sixth intensively detailed historical atlas and his eighth book, Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (D&M $49.95), traces the region's development from the days when Vancouver's predecessor, the village of Granville, with 30 buildings, was divided into lots in 1882 for a city to be called Liverpool. It received the Lieutenant Governor's Medal for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation.

The indefatigable Hayes--easily one of the province's leading authors even though you never see him at Writers Festivals--continued his bestselling historical atlas series with Historical Atlas of Early Railways, examining rail travel from its beginnings-when carts caused ruts in roads as early as 2200 BCE-to the 20th century. Some 320 maps and 450 photos trace the evolution of rail travel with Hayes' usual diligence and passion.

British Columbia was brought into the Canadian Confederation in 1871 in exchange for the promise of a transcontinental line to the West Coast. When the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1886, it bolstered economic development in the province, created the city of Vancouver and spurred others to build competing lines. In his prolifically illustrated Iron Road West (Harbour $44.95) Derek Hayes charts the development of the province through its competitive railway lines and he explores the emergence of the modern freight railway in British Columbia, including fully automated and computerized trains.

[Other geography authors of B.C. include Atkeson, Ray; Barnes, Trevor; Berelowitz, Lance; Blomley, Nick; Cameron, Laura Jean; Clapp, C.H.; Forward, Charles N.; Fraser, William Donald; Gregory, Derek; Gunn, Angus; Halseth, Greg; Hardwick, Walter G.; Harris, Cole; Holbrook, Stewart; Kistritz, Ron; Koroscil, Paul M.; Lai, David; Leigh, Roger; McGillivray, Brett; Minghi, Julian; O'Neill, Thomas; Penlington, Norman; Pierce, John; Robinson, J. Lewis; Sandwell, R.W.; Slaymaker, Olav; Townsend-Gault, Ian; Wilson, James W. (Jim); Wynn, Graeme; Yorath, Christopher John.] @2010.

Review of the author's work by BC Studies:

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas

Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley

Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest: Maps of Exploration

BOOKS:

Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. (Cavendish, 1999) 1-55289-900-4

Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2001)

First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition Across North America, and the Opening of the Continent (Douglas & McIntyre)

Historical Atlas of Canada: Canada's History Illustrated with Original Maps (Douglas & McIntyre)

Historical Atlas of the Arctic (Douglas & McIntyre, 2003) 1-55365-004-2 : $75.00

Canada: An Illustrated History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004) 1-55365-046-8: $55.00

America Discovered: A Historical Atlas of Exploration. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004) 1-55365-049-2 : $65.00

Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (Douglas & McIntyre, 2005) 1-55365-107-3

Historical Atlas of the United State (Douglas & McIntyre, 2006). 1-55365-205-3 : $55.00.

Historical Atlas of Toronto (Douglas & McIntyre, 2008)

Historical Atlas of the North American Railroad. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010). 978-1-55365-553-2 : $49.95

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012). $59.95 978-1-926812-57-1

Historical Atlas of Canada: Canada's History Illustrated with Original Maps (Revised Edition) (Douglas & McIntyre, 2015) $34.95 978-1-77162-079-6

Historical Atlas of Early Railways (D&M, 2017) $49.95 978-1-77162-175-5

Iron Road West (Harbour, 2018) $44.95 978-1-550178388

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (D&M, 2019) $44.95 978-1-77162-211-0

Incredible Crossings: The History and Art of the Bridges, Tunnels and Ferries That Connect British Columbia (Harbour, 2022) $46.95 978-1550179903

[BCBW 2022]

DEREK HAYES STAYS ON TRACK -- From Ormsby Review

Iron Road West: An Illustrated History of British Columbia’s Railways

by Derek Hayes

Madeira Park: Harbour: 2018

$44.95 / 9781550178388

Reviewed by Walter Volovsek

*

Derek Hayes’ latest venture into railway history is focused entirely on British Columbia. Although thus limited geographically, Hayes spins a very rich and comprehensive account of railway development in the province, from the first surveys for the “National Dream” that would bind us to the rest of Canada, to the final fruition of rail transport in largely automated modern trains and highly efficient urban transit systems.

Derek Hayes’ latest venture into railway history is focused entirely on British Columbia. Although thus limited geographically, Hayes spins a very rich and comprehensive account of railway development in the province, from the first surveys for the “National Dream” that would bind us to the rest of Canada, to the final fruition of rail transport in largely automated modern trains and highly efficient urban transit systems.

The first challenge is well presented. Politics stalled the development of our first transcontinental railway until the re-election of John A. Macdonald in 1878 and the subsequent contract between the dominion government and the newly incorporated Canadian Pacific Railway Company, signed in 1881.

As rails were advanced westward across the prairies Andrew Onderdonk tackled the difficult Fraser Canyon. The discovery in 1882 of a pass through the Selkirks by Major A.B. Rogers committed the line to a difficult penetration through the mountains and various challenges in tackling serious grades. Avalanches were another problem, especially in Rogers Pass. Much subsequent effort went into the construction of snow sheds and later tunnelling to remove the vulnerable line from the pass. While dealing with these difficulties, the railway company capitalized on the fabulous mountain scenery and constructed deluxe hotels to promote tourism.

The second decade of the 20th Century saw the birth of two more transcontinental railways: The Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern. Both took advantage of the much gentler Yellowhead Pass across the continental divide that totally avoided the Selkirks. Grand Trunk Pacific boasted a grade no greater than 0.5 percent, compared with the 2.2 percent the CPR still had to contend with, even after various improvements. Its terminus at Prince Rupert has the advantage of being some 600 km closer to Asian destinations. The Great War created many additional problems for both lines leading them into bankruptcy and government takeover. They became components of the Canadian National Railway.

The same period saw the completion of the CPR southern line through the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway. Components of it had been built previously to take advantage of easier grades through the Crowsnest Pass, and the coalfields discovered nearby. The line initially ended at Kootenay Landing, with steamers filling the gap to Nelson. The very first part of the southern line was built from Sproat’s Landing, just across the Columbia River from my home, to Nelson. This was the line that CPR president Van Horne derided as “a railway from nowhere to nowhere.” The next link was provided by American smelter baron F.A. Heinze with his Columbia & Western charter. Those developments are well described in the book.

I must, however, express a bit of disappointment with the extension of the Columbia & Western Railway from West Robson to Midway being given only one line, and even that not being fully correct. Heinze completed his railway between Trail and West Robson in 1897, and this was a standard gauge line, unlike its steeper component that linked Trail to Rossland. Both were sold to the CPR the following spring, along with Heinze’s smelter, which proved exceedingly profitable to the railway company in the long run, giving it not only leverage to far-flung mining interests, but also to the control of power development on the Kootenay River.

The extension of the line westward to tap the mineral wealth of the Boundary was an epic accomplishment all by itself. Astonishing trestles stapled it to the precipitous hillsides, and its admirable quarried stone retaining walls, bridge abutments, and culverts mirror the technical achievements on the mainline through Rogers Pass. When completed, Bull Dog Tunnel was the longest in B.C. The line’s later extension (as the KVR) to the Okanagan and beyond failed to present those aspects of craftsmanship and durability. The Columbia River crossing (which joins the Columbia & Western with the Columbia & Kootenay) still displays those granite piers and bridge abutments, and features the turn span that is a twin of the one formerly incorporated in the Kitsilano trestle across False Creek, now gone.

Incidentally, the twinned Highway 3 tunnel near Greenwood (p. 149) was built in the 1960s to accommodate new road alignment. When it and the rail bed were removed some 30 years later, the original 1912 highway tunnel was exposed; it had been constructed through the original wooden trestle prior to both being buried by the fill. The older tunnel was left as a piece of heritage; it bears marks of the original trestle components. The two tunnels, however, were not linked in any way.

My interest in this line is admittedly biased, as I have been developing interpretive infrastructure for what is now the Columbia & Western Rail Trail. It and the line up the Slocan Valley were donated by the CPR to the Trans Canada Trail Society at the eleventh hour, and were instrumental in shifting what is now known as The Great Trail from the lacklustre Dewdney Trail to its much more scenic and historically richer competitor.

The complex evolution of the provincial railway, whose mandate was to tap the resources of central and northern B.C., is well documented. It was born as the Pacific Great Eastern under the McBride government in 1912, and — crippled by the Great War — was taken over by the government of his successor. Up to that time it consisted of two disconnected segments: a working line between North Vancouver and Whytecliff, and a segment being pushed northward from Squamish. The southern segment was closed in 1928, while the northern segment was advanced gradually until work was stopped 30 km short of Prince George and the rails removed back to Quesnel. That section was rebuilt and tracks connected to Prince George in 1952.

The missing segment along Howe Sound was blasted from the precipitous mountainside by 1956, and West Vancouver residents were chagrined to have to revert to the disruption of train traffic again, much of it now industrial. The government of W.A.C. Bennett pushed the line further north to keep competing railways from tapping the vast resources of northeastern B.C. from Alberta. Feeder lines were built in all directions, and an extension pushed into the northwest corner. In 1972 the name was changed to the British Columbia Railway. The transformation was completed when the provincial government sold the line to Canadian National in 2004.

Although most railways discussed are standard gauge lines, there were some notable exceptions. J.J. Hill managed to put the Kaslo & Slocan Railway directly into Sandon, ahead of the CPR. The line, however, did not last long as natural disasters and a forest fire put an end to the operation in 1910. The CPR rebuilt part of the line at a lower elevation, converted the remainder to standard gauge and connected it to their line from Nakusp at Three Forks.

Another narrow gauge railway was the White Pass & Yukon Railway, built to provide easier access to the Yukon gold fields from the head of Lynn Canal. It required three separate charters as it passed through three jurisdictions. The Klondike gold rush was winding down by the time it was completed to Whitehorse in 1900; however there was enough demand to keep it in operation. Part of the line is still in service as a heritage railway.

This encyclopaedic work includes chapters on all aspects of railway development. The application of the steam locomotive to specialized industrial applications such as mining and logging is well documented in a dedicated chapter. Specialized locomotives were utilized to follow the tighter curves and uneven grades of the more primitive and transient logging railways. Greater torque was supplied to the traction wheels by geared drive shafts, resulting in more pulling power. Three basic designs were employed; of these, the Shay locomotive is probably best known. Underground mining applications had to consider the possibility of explosion and for that reason steam power was out. Traction engines were either electric or run by compressed air contained in a large tank.

Many intriguing details about the silk trains (which took priority over everything else), armoured trains (to fight off a Japanese invasion), and other types of special trains are presented to amuse the reader. In this category, Charles Glidden’s special train from Minneapolis to Vancouver takes the cake. He had his motor car fitted with flanged wheels and drove it all the way, with the mandatory conductor along.

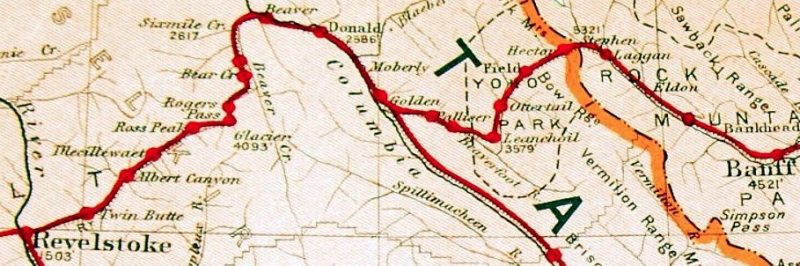

Having produced various atlases of historic maps, it is only natural for Derek Hayes to include a well-chosen collection. I had to rig up a strong magnifying glass to examine the finer details, but the cartography adds another dimension to this comprehensive work. Also in this category are a couple of sections called Tracing the Path of an Old Railway, where the author matches information gleaned from old maps to the current landscape. Photographs match the current views to locations on the long-vanished rail lines.

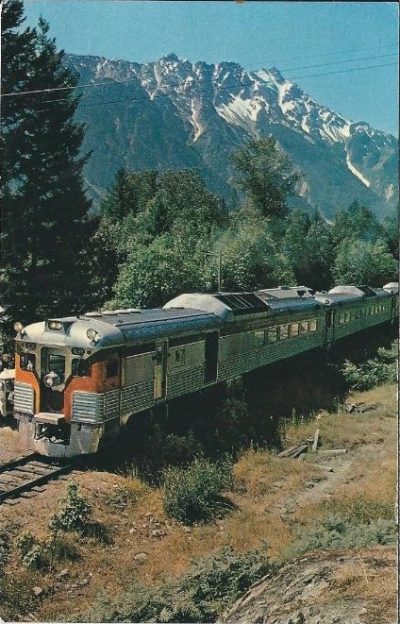

The book ends triumphantly in the section “A Legacy Preserved.” Many excellent colour photographs document the preservation of railway history in B.C., from still functioning heritage trains to exotic static displays of rolling stocks and other artefacts in railway museums. It is obvious that Hayes is not only extremely knowledgeable in all aspects of railroading, but is also an accomplished photographer. Perfect composition, great lighting, and sharp focus are characteristic of his photographs, not all of which were taken under ideal conditions. Their skilful arrangement in the book is a feast for the eye.

Iron Road West: An Illustrated History of British Columbia’s Railways is not only a worthy addition to the reference library of the seasoned railway buff, but it also serves as an intriguing coffee table conversation prop for the amateur historian.

*

After studying medicine and managing the biology labs at Selkirk College for 24 years, Walter O. Volovsek retired to a second voluntary career: developing walking and ski touring trails for the Castlegar community. Most of these are also presented to the user as conduits into the past by means of interpretive signage and related essays on his website www.trailsintime.org. This led to connections with descendants of important Castlegar pioneers, and in 2012 Walter self-published his biography of Castlegar founder Edward Mahon, The Green Necklace: The Vision Quest of Edward Mahon (Otmar Publishing, 2012). Mahon was also known for his legacy of parks and greenways in North Vancouver. Walter has also written a book on his trail-building efforts, Trails in Time: Reflections (Otmar, 2012), and has been commissioned to develop signs in key locations including Castlegar Millennium Park, Castlegar Spirit Square, and Brilliant Bridge Regional Park. Walter currently writes a history column for the Castlegar News.

*

If geography were an Olympic event, they'd accuse Derek Hayes of being on steroids. During the first decade of the new millennium, Hayes compiled, designed and wrote ten atlases and illustrated histories, starting with his self-published Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (1999), winner of the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award. Since that debut, Hayes has won many awards for tracing the exploration and settlement patterns of areas throughout Canada and the U.S.

These were followed by British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012), winner of three major awards: the inaugural Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize, the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize to recognize the author of the book that contributes most to the enjoyment and understanding of British Columbia, and the Lieutenant Governor's Award for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation. It was also shortlisted for the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award presented to the originating publisher and author(s) of the best book in terms of public appeal, initiative, design, production and content.

The first Hayes atlas was followed by Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (2001) and First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition across North America, and the Opening of the Continent (2001). With 370 maps charting the growth of Vancouver and its environs, Hayes' sixth large format atlas, and his eighth book, Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (2005), traces the region's development from the days when the village of Granville, with 30 buildings, was divided into lots in 1882 for a city to be called Liverpool. Hayes received the Lieutenant Governor's Medal for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation.

British Columbia was brought into the Canadian Confederation in 1871 in exchange for the promise of a transcontinental line to the West Coast. When the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1886, it bolstered economic development in the province, created the city of Vancouver and spurred others to build competing lines. In his prolifically illustrated Iron Road West (Harbour $44.95) Derek Hayes charts the development of the province through its competitive railway lines and he explores the emergence of the modern freight railway in British Columbia, including fully automated and computerized trains. 978-1-550178388

"I collected stamps as a child," Hayes explains, "and I wanted to know where they all came from, hence out came the atlas. Then I got into geography academically, then city planning. I like to think that if a picture is worth a thousand words, a map must be worth ten thousand. Having said that, I would emphasize I try to write history using maps as the primary illustration. This has a wider audience than if I only wrote books about maps."

FULL ENTRY:

Born in England, Derek Hayes came to UBC to undertake graduate work at the Geography department in 1969, having trained as a geographer at the University of Hull in England. His interest in botanical geography led him to import hobby greenhouses. A greenhouse contact in England then suggested he become the Canadian distributor for a series of gardening books. At first, the gardening titles by experts sold poorly. Then they were spotted at the PNE garden show by an avid B.C. gardener, Bill Vander Zalm, who encouraged the Art Knapp outlets throughout B.C. to carry Hayes' titles. Based in Delta, Cavendish Books subsequently produced more than 100 of its own mainly gardening-related books. This publishing success led Hayes to finally indulge his passion for maps.

In 1999 Hayes published his Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Cavendish). This first atlas received the Bill Duthie Booksellers Choice Award in 2000. "Quite frankly I had no idea that anybody in B.C other than myself was interested in maps," said Hayes, upon receiving the prize. "Luckily there were quite a few! The book contains lots of speculative maps about British Columbia because British Columbia is one of the last places in the world, other than the poles, to be put on the map of the world. Cartographers didn't like to have blanks on their maps. If they didn't know what was out there, they made it up. As a result there are some bizarre maps of what is now British Columbia. On one there is a great sea of the west that goes as far as Kansas. On another a Northwest Passage takes off somewhere near Prince Rupert and goes to Hudson's Bay. It's wild and it's woolly."

Hayes' Historical Atlas of Canada received the 2003 Lela Common Award for Canadian History from the Canadian Authors Association (and a revised edition was published in 2015). It was preceded by a study of Alexander Mackenzie and the Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (Douglas & McIntyre). "I've been collecting maps for 30 years," said Hayes, who says he spent more than $20,000 on reproduction fees. "The Russian ones were particularly difficult to track. It's been like detective work." The North Pacific atlas provides 235 maps that pertain directly to the territory now known as B.C. and 320 maps in all. Included are the voyages of Vitus Bering, the first map of the entire southern interior of B.C. made by Archibald McDonald in 1827, maps from the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1841, military spy maps of 1845 and 1846, American railroad surveys, British-American Boundary Commission maps, gold rush maps and maps for the purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867.

Hayes' British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012) was shortlisted for the inaugural Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize and the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize to recognize the author(s) of the book that contributes most to the enjoyment and understanding of British Columbia. It was also shortlisted for the Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award presented to the originating publisher and author(s) of the best book in terms of public appeal, initiative, design, production and content.

As an historian who uses maps as an adjunct to his work, Hayes has also produced an illustrated history of Canada, to be followed by a similar work for the United States. He is involved in his own books as a designer, and has won three Alcuin Awards for his work as a packager of his own materials. With 370 maps charting the growth of Vancouver and its environs, Derek Hayes' sixth intensively detailed historical atlas and his eighth book, Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (D&M $49.95), traces the region's development from the days when Vancouver's predecessor, the village of Granville, with 30 buildings, was divided into lots in 1882 for a city to be called Liverpool. It received the Lieutenant Governor's Medal for best B.C. history book from the B.C. Historical Federation.

The indefatigable Hayes--easily one of the province's leading authors even though you never see him at Writers Festivals--continued his bestselling historical atlas series with Historical Atlas of Early Railways, examining rail travel from its beginnings-when carts caused ruts in roads as early as 2200 BCE-to the 20th century. Some 320 maps and 450 photos trace the evolution of rail travel with Hayes' usual diligence and passion.

British Columbia was brought into the Canadian Confederation in 1871 in exchange for the promise of a transcontinental line to the West Coast. When the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1886, it bolstered economic development in the province, created the city of Vancouver and spurred others to build competing lines. In his prolifically illustrated Iron Road West (Harbour $44.95) Derek Hayes charts the development of the province through its competitive railway lines and he explores the emergence of the modern freight railway in British Columbia, including fully automated and computerized trains.

[Other geography authors of B.C. include Atkeson, Ray; Barnes, Trevor; Berelowitz, Lance; Blomley, Nick; Cameron, Laura Jean; Clapp, C.H.; Forward, Charles N.; Fraser, William Donald; Gregory, Derek; Gunn, Angus; Halseth, Greg; Hardwick, Walter G.; Harris, Cole; Holbrook, Stewart; Kistritz, Ron; Koroscil, Paul M.; Lai, David; Leigh, Roger; McGillivray, Brett; Minghi, Julian; O'Neill, Thomas; Penlington, Norman; Pierce, John; Robinson, J. Lewis; Sandwell, R.W.; Slaymaker, Olav; Townsend-Gault, Ian; Wilson, James W. (Jim); Wynn, Graeme; Yorath, Christopher John.] @2010.

Review of the author's work by BC Studies:

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas

Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley

Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest: Maps of Exploration

BOOKS:

Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. (Cavendish, 1999) 1-55289-900-4

Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2001)

First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition Across North America, and the Opening of the Continent (Douglas & McIntyre)

Historical Atlas of Canada: Canada's History Illustrated with Original Maps (Douglas & McIntyre)

Historical Atlas of the Arctic (Douglas & McIntyre, 2003) 1-55365-004-2 : $75.00

Canada: An Illustrated History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004) 1-55365-046-8: $55.00

America Discovered: A Historical Atlas of Exploration. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004) 1-55365-049-2 : $65.00

Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley (Douglas & McIntyre, 2005) 1-55365-107-3

Historical Atlas of the United State (Douglas & McIntyre, 2006). 1-55365-205-3 : $55.00.

Historical Atlas of Toronto (Douglas & McIntyre, 2008)

Historical Atlas of the North American Railroad. (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010). 978-1-55365-553-2 : $49.95

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012). $59.95 978-1-926812-57-1

Historical Atlas of Canada: Canada's History Illustrated with Original Maps (Revised Edition) (Douglas & McIntyre, 2015) $34.95 978-1-77162-079-6

Historical Atlas of Early Railways (D&M, 2017) $49.95 978-1-77162-175-5

Iron Road West (Harbour, 2018) $44.95 978-1-550178388

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (D&M, 2019) $44.95 978-1-77162-211-0

Incredible Crossings: The History and Art of the Bridges, Tunnels and Ferries That Connect British Columbia (Harbour, 2022) $46.95 978-1550179903

[BCBW 2022]

DEREK HAYES STAYS ON TRACK -- From Ormsby Review

Moving amid the mountains

November 17th, 2018

Iron Road West: An Illustrated History of British Columbia’s Railways

by Derek Hayes

Madeira Park: Harbour: 2018

$44.95 / 9781550178388

Reviewed by Walter Volovsek

*

Derek Hayes’ latest venture into railway history is focused entirely on British Columbia. Although thus limited geographically, Hayes spins a very rich and comprehensive account of railway development in the province, from the first surveys for the “National Dream” that would bind us to the rest of Canada, to the final fruition of rail transport in largely automated modern trains and highly efficient urban transit systems.

Derek Hayes’ latest venture into railway history is focused entirely on British Columbia. Although thus limited geographically, Hayes spins a very rich and comprehensive account of railway development in the province, from the first surveys for the “National Dream” that would bind us to the rest of Canada, to the final fruition of rail transport in largely automated modern trains and highly efficient urban transit systems.The first challenge is well presented. Politics stalled the development of our first transcontinental railway until the re-election of John A. Macdonald in 1878 and the subsequent contract between the dominion government and the newly incorporated Canadian Pacific Railway Company, signed in 1881.

As rails were advanced westward across the prairies Andrew Onderdonk tackled the difficult Fraser Canyon. The discovery in 1882 of a pass through the Selkirks by Major A.B. Rogers committed the line to a difficult penetration through the mountains and various challenges in tackling serious grades. Avalanches were another problem, especially in Rogers Pass. Much subsequent effort went into the construction of snow sheds and later tunnelling to remove the vulnerable line from the pass. While dealing with these difficulties, the railway company capitalized on the fabulous mountain scenery and constructed deluxe hotels to promote tourism.

The second decade of the 20th Century saw the birth of two more transcontinental railways: The Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern. Both took advantage of the much gentler Yellowhead Pass across the continental divide that totally avoided the Selkirks. Grand Trunk Pacific boasted a grade no greater than 0.5 percent, compared with the 2.2 percent the CPR still had to contend with, even after various improvements. Its terminus at Prince Rupert has the advantage of being some 600 km closer to Asian destinations. The Great War created many additional problems for both lines leading them into bankruptcy and government takeover. They became components of the Canadian National Railway.

The same period saw the completion of the CPR southern line through the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway. Components of it had been built previously to take advantage of easier grades through the Crowsnest Pass, and the coalfields discovered nearby. The line initially ended at Kootenay Landing, with steamers filling the gap to Nelson. The very first part of the southern line was built from Sproat’s Landing, just across the Columbia River from my home, to Nelson. This was the line that CPR president Van Horne derided as “a railway from nowhere to nowhere.” The next link was provided by American smelter baron F.A. Heinze with his Columbia & Western charter. Those developments are well described in the book.

I must, however, express a bit of disappointment with the extension of the Columbia & Western Railway from West Robson to Midway being given only one line, and even that not being fully correct. Heinze completed his railway between Trail and West Robson in 1897, and this was a standard gauge line, unlike its steeper component that linked Trail to Rossland. Both were sold to the CPR the following spring, along with Heinze’s smelter, which proved exceedingly profitable to the railway company in the long run, giving it not only leverage to far-flung mining interests, but also to the control of power development on the Kootenay River.

The extension of the line westward to tap the mineral wealth of the Boundary was an epic accomplishment all by itself. Astonishing trestles stapled it to the precipitous hillsides, and its admirable quarried stone retaining walls, bridge abutments, and culverts mirror the technical achievements on the mainline through Rogers Pass. When completed, Bull Dog Tunnel was the longest in B.C. The line’s later extension (as the KVR) to the Okanagan and beyond failed to present those aspects of craftsmanship and durability. The Columbia River crossing (which joins the Columbia & Western with the Columbia & Kootenay) still displays those granite piers and bridge abutments, and features the turn span that is a twin of the one formerly incorporated in the Kitsilano trestle across False Creek, now gone.

Incidentally, the twinned Highway 3 tunnel near Greenwood (p. 149) was built in the 1960s to accommodate new road alignment. When it and the rail bed were removed some 30 years later, the original 1912 highway tunnel was exposed; it had been constructed through the original wooden trestle prior to both being buried by the fill. The older tunnel was left as a piece of heritage; it bears marks of the original trestle components. The two tunnels, however, were not linked in any way.

My interest in this line is admittedly biased, as I have been developing interpretive infrastructure for what is now the Columbia & Western Rail Trail. It and the line up the Slocan Valley were donated by the CPR to the Trans Canada Trail Society at the eleventh hour, and were instrumental in shifting what is now known as The Great Trail from the lacklustre Dewdney Trail to its much more scenic and historically richer competitor.

The complex evolution of the provincial railway, whose mandate was to tap the resources of central and northern B.C., is well documented. It was born as the Pacific Great Eastern under the McBride government in 1912, and — crippled by the Great War — was taken over by the government of his successor. Up to that time it consisted of two disconnected segments: a working line between North Vancouver and Whytecliff, and a segment being pushed northward from Squamish. The southern segment was closed in 1928, while the northern segment was advanced gradually until work was stopped 30 km short of Prince George and the rails removed back to Quesnel. That section was rebuilt and tracks connected to Prince George in 1952.

The missing segment along Howe Sound was blasted from the precipitous mountainside by 1956, and West Vancouver residents were chagrined to have to revert to the disruption of train traffic again, much of it now industrial. The government of W.A.C. Bennett pushed the line further north to keep competing railways from tapping the vast resources of northeastern B.C. from Alberta. Feeder lines were built in all directions, and an extension pushed into the northwest corner. In 1972 the name was changed to the British Columbia Railway. The transformation was completed when the provincial government sold the line to Canadian National in 2004.

Although most railways discussed are standard gauge lines, there were some notable exceptions. J.J. Hill managed to put the Kaslo & Slocan Railway directly into Sandon, ahead of the CPR. The line, however, did not last long as natural disasters and a forest fire put an end to the operation in 1910. The CPR rebuilt part of the line at a lower elevation, converted the remainder to standard gauge and connected it to their line from Nakusp at Three Forks.

Payne Bluff on the Kaslo & Slocan Railway near Sandon, circa 1900. R.H. Trueman photo, City of Vancouver Archives

Another narrow gauge railway was the White Pass & Yukon Railway, built to provide easier access to the Yukon gold fields from the head of Lynn Canal. It required three separate charters as it passed through three jurisdictions. The Klondike gold rush was winding down by the time it was completed to Whitehorse in 1900; however there was enough demand to keep it in operation. Part of the line is still in service as a heritage railway.

This encyclopaedic work includes chapters on all aspects of railway development. The application of the steam locomotive to specialized industrial applications such as mining and logging is well documented in a dedicated chapter. Specialized locomotives were utilized to follow the tighter curves and uneven grades of the more primitive and transient logging railways. Greater torque was supplied to the traction wheels by geared drive shafts, resulting in more pulling power. Three basic designs were employed; of these, the Shay locomotive is probably best known. Underground mining applications had to consider the possibility of explosion and for that reason steam power was out. Traction engines were either electric or run by compressed air contained in a large tank.

Many intriguing details about the silk trains (which took priority over everything else), armoured trains (to fight off a Japanese invasion), and other types of special trains are presented to amuse the reader. In this category, Charles Glidden’s special train from Minneapolis to Vancouver takes the cake. He had his motor car fitted with flanged wheels and drove it all the way, with the mandatory conductor along.

Having produced various atlases of historic maps, it is only natural for Derek Hayes to include a well-chosen collection. I had to rig up a strong magnifying glass to examine the finer details, but the cartography adds another dimension to this comprehensive work. Also in this category are a couple of sections called Tracing the Path of an Old Railway, where the author matches information gleaned from old maps to the current landscape. Photographs match the current views to locations on the long-vanished rail lines.

The book ends triumphantly in the section “A Legacy Preserved.” Many excellent colour photographs document the preservation of railway history in B.C., from still functioning heritage trains to exotic static displays of rolling stocks and other artefacts in railway museums. It is obvious that Hayes is not only extremely knowledgeable in all aspects of railroading, but is also an accomplished photographer. Perfect composition, great lighting, and sharp focus are characteristic of his photographs, not all of which were taken under ideal conditions. Their skilful arrangement in the book is a feast for the eye.

Iron Road West: An Illustrated History of British Columbia’s Railways is not only a worthy addition to the reference library of the seasoned railway buff, but it also serves as an intriguing coffee table conversation prop for the amateur historian.

*

After studying medicine and managing the biology labs at Selkirk College for 24 years, Walter O. Volovsek retired to a second voluntary career: developing walking and ski touring trails for the Castlegar community. Most of these are also presented to the user as conduits into the past by means of interpretive signage and related essays on his website www.trailsintime.org. This led to connections with descendants of important Castlegar pioneers, and in 2012 Walter self-published his biography of Castlegar founder Edward Mahon, The Green Necklace: The Vision Quest of Edward Mahon (Otmar Publishing, 2012). Mahon was also known for his legacy of parks and greenways in North Vancouver. Walter has also written a book on his trail-building efforts, Trails in Time: Reflections (Otmar, 2012), and has been commissioned to develop signs in key locations including Castlegar Millennium Park, Castlegar Spirit Square, and Brilliant Bridge Regional Park. Walter currently writes a history column for the Castlegar News.

*

Articles: 8 Articles for this author

First Crossing (D&M $35)

Info

Derek Hayes' coffee table book First Crossing (D&M $35) extensively recalls Mackenzie's crossing and the opening of the continent with an array of maps. 1-55054-994-4

[SUMMER 2003 BCBW]

Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (D&M)

Info

Following his award-winning Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, Derek Hayes' Historical Atlas of the North Pacific Ocean (D&M) is an illustrated account of scientific ocean exploration over the past 500 years.

[BCBW WINTER 2001]

Historical Atlas of the Arctic (D&M $75)

Article

Derek Hayes continues his remarkable spate of atlases with the Historical Atlas of the Arctic (D&M $75), documenting with maps and commentary how expeditions sought the North Pole on foot, by hot air balloon and by airplane. In quick succession Hayes has released in-depth compendia of maps and history for Canada, the North Pacific Ocean and for British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. He has just received the Lela Common Award for Canadian History from the Canadian Authors Association. 1-55365-004-2

[BCBW 2003]

First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition Across North America, and the Opening of the Continent

Review

The idea of a navigable route from the Atlantic Ocean or Hudson Bay to the fabulous riches of Cathay took hold in Europe during the 17th century as a variation on the quest for a Northwest Passage. If a strait or channel couldn't be found leading to China, Japan and the Spice Islands, then surely a great 'River of the West' would provide the necessary access.

In the early 1770s fur-trader Samuel Hearne demonstrated, for all but the obsessively deluded, that no strait crossed the continent south of the Arctic Ocean. In 1778, Captain James Cook clarified the scope of the challenge by establishing the position of the west coast as considerably farther west than anyone had imagined. Enter Alexander Mackenzie.

In 1785, this doughty Scot began wintering west of the Great Lakes. Two years later, Mackenzie, an ambitious partner with the North West Company, moved into Athabasca country. From there, inspired by the geographical speculations of Peter Pond (a fellow fur-trader "of dubious character"), Mackenzie began seeking the elusive great River of the West.

In 1789, from Great Slave Lake in the heart of what is today the Northwest Territories, Mackenzie led a canoe expedition down the river that now bears his name. It flowed west and then, to his consternation, veered north, taking him all the way to the Arctic Ocean. He unwittingly became only the second European, after Hearne, to reach the northern coast of the continent.

Four years later, canoeing west out of Lake Athabasca, in northern Alberta and Saskatchewan, Mackenzie tried again. After a strenuous voyage via the Peace, Parsnip, Fraser and West Road rivers, he reached the tidewaters of the Pacific Ocean near Bella Coola.

Now Derek Hayes, rightly admired for his B.C. Book Prize-winning Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, has produced First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition Across North America, and the Opening of the Continent (D&M $50).

The title suggests its thesis: Twelve years before the celebrated American expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, Alexander Mackenzie became the first person to cross the North American continent north of Mexico. Hayes traces the fur-trader's accomplishment with an attention to detail that should satisfy specialists.

The book is chiefly concerned with Mackenzie and geography, but Hayes ensures Mackenzie's character is also revealed. Mackenzie writes, "...being endowed by Nature with an inquisitive mind and an enterprising spirit; possessing also a constitution and frame of body equal to the most arduous undertakings, and being familiar with toilsome exertions in the prosecution of mercantile pursuits, I not only contemplated the practicability of penetrating across the continent of America, but was confident in the qualifications. ..to undertake the perilous enterprise." Apparently Mackenzie only lacked an editor.

Considerable expertise and resources have been applied to make this splendid book

attractive to a broad general audience, mainly through the use of illustrations, many extending over two pages, and informational sidebars. The roughly 200 illustrations include historical and contemporary photos, engravings, paintings and numerous early maps, many of them speculative. Here we find, published for the first time, the only surviving copy of any maps actually drawn during either of Mackenzie's voyages. One small problem does arise: Hayes analyzes some of the maps in detail, and the book's reproductions, while excellent, are frequently too small to read with the naked eye. Maybe it's just me?

The sidebars focus on everything from pemmican to fixing the precise position of Fort Chipewyan; from country marriages to canoeing in the dark. Oh, and don't miss the vivid description, taken from the diary of a young army engineer, of Mackenzie and his pals succumbing to "the old Highland drinking propensity" and, with great good cheer, drinking themselves under the table.

Hayes is strongest not on social background but on historical and geographical context. In a book about Mackenzie's voyages, he devotes most of an early chapter to Samuel Hearne's singular trek, and much of a later one to the overland expeditions of Sir .John Franklin.

Apart from a tiny miscue (referring to the 16th century when he means the 15th) the only blunder Hayes makes is when he repeats the canard that the reprehensible Robert McClure "made" the final link in the Northwest Passage. This notion is refuted --once and for all, I hope-in Fatal Passage, my own recent book about explorer .John Rae.

Hayes notes that a rugged overland journey of 180 miles (285 km), which Mackenzie covered first in 12 days and later in eight, today takes an expert hiker fifteen days. Yikes! He demonstrates extensive knowledge of his material by mentioning, for example, that the "English Chief" who guided Mackenzie on his first voyage was a Chipewyan named Nestabeck who had once travelled with Hearne's guide, the peerless Matonabbee.

Hayes also squarely addresses the "question of whether Mackenzie 'discovered' anything considering that the places he visited had all been 'discovered' by indigenous peoples..."; His answer? Yes.

Without denigrating the experience of native peoples, he argues convincingly that discovery is dependent on motivation, on vision: a Northwest Passage could only be "discovered" after it had been conceived.

That Alexander Mackenzie discovered no commercially viable River to the West is irrelevant: Cathay was a myth, the fur trade is history and such a river does not exist. First Crossing celebrates an explorer who helped define Canada, both physically and psychologically. That, surely, is enough.1-55054-866-2

Ken McGoogans Fatal Passage: The Untold Story of John Rae, the Arctic Adventurer Who Discovered the Fate of Franklin, has been nominated for the Drainie- Taylor Biography Prize. He is working on a book about Samuel Hearne.

[BCBW Spring 2002]

The Passionate Geographer

Interview

If geography was an Olympic event, they'd say Derek Hayes was on steroids. With seven large-format titles in five years, he's easily one of Canada's most industrious his-torians. Hayes has designed every page of his new coffee table books-Canada: An Illustrated History (D&M $55) and America Discovered: Historical Atlas of Exploration (D&M $65). He's won three Alcuin Design Awards and a Bill Duthie Booksellers' Choice Award since his debut in 1999.

BCBW: How did you develop your love for maps in the first place?

HAYES: I collected stamps as a child and I wanted to know where they all came from, hence out came the atlas. Then I got into geography academically, then city planning. I like to think that if a picture is worth a thousand words, a map must be worth ten thousand. Having said that, I would emphasize I try to write history using maps as the primary illustration. This has a wider audience than if I only wrote books about maps.

BCBW: Is research ever a burden or do you have an overwhelming passion for it?

HAYES: I love the thrill of tracking down information. I love the myriad of little things that you need to find in order to make your history relevant and alive. Finding out why something happened, what motivated an action or a policy, and I love discovering the original items that document them. Perhaps something signed or written or drawn so long ago, maybe under adverse conditions, and here it is in your hand! That the document survived at all is often a minor miracle. You do, however, come to a realization that there was a lot of material that never survived, was lost or destroyed before it was considered significant. We are beholden to the historical hoarders of the past.

BCBW: Beyond hard work, what's the secret to producing more than one book per year?

HAYES: Well, when I visit a particular library or archive, I try to collect maps for more than one book. For instance, when I was in several French archives last year, doing research for America Discovered, I collected maps and information for another book I have in preparation, a historical atlas of the United States. Books are often in gestation for quite a long time. The Historical Atlas of Canada involved three separate visits to the vaults of the National Archives of Canada [now Library and Archives of Canada].

BCBW: Personally, what did you get to 'discover' for America Discovered?

HAYES: I saw parts of the continent I hadn't previously visited, such as the Outer Banks of North Carolina and Roanoke Island. This was the site of the first attempts to found an English colony in America, promoted by Sir Walter Raleigh in the 1580s. One could easily imagine finding oneself on an unknown shore, surrounded by overwhelming numbers of not always friendly native people.

BCBW: How does your illustrated history of Canada differ from the Historical Atlas of Canada?

HAYES: The new book includes facets of social history, not just the main story line of mainstream Canadian history, and it's illustrated with all manner of images, not just photos and paintings and maps, but also posters, stamps, cartoons, and even stained glass windows and a tapestry. There are also a number of never-before-published paintings from the Winkworth Collection, recently acquired by the National Archives. It's been a challenge to come up with the right mix of iconic and must-include images with the rarely-seen.

BCBW: Is there some mysterious map that you're craving to see?

HAYES: I have spent an inordinate amount of time trying to track down the original maps of the Norwegian explorer, Otto Sverdrup, who discovered Canada's Far North in 1898-1902. He claimed it for Norway. This caused a furor in the Canadian government, and a number of expeditions were sent out specifically to claim sovereignty in the Arctic. In 1930 the government did a deal with Sverdrup and the Norwegian government whereby they purchased Sverdrup's maps and diaries for the then amazing sum of $67,000. They were able to presume Sverdrup had been working for Canada all the time and thus there could be no challenges to Canadian sovereignty in the region he discovered. But, despite an act of parliament to come up with the $67,000 (and this at the beginning of the Depression) and their significance to Canadian sovereignty, no one can find Sverdrup's maps. The diaries were returned to Sverdrup's family, but his granddaughter cannot recall any maps coming back. And they are not in the Norwegian National Library where the diaries are, still with their Department of the Interior stamp. Why would such important maps to Canada go missing? I wish I knew the answer.

BCBW: Men are notorious for not asking for directions when they go somewhere in a car; whereas women are more sensible about asking questions and using a map. True or false?

HAYES: [Laughter] I really don't know about that. I can only tell you that about 90% of the subscribers to the [now defunct] magazine about maps, Mercator's World, were male, and over 80% of the members of the Map Society of British Columbia are male. You're free to draw any conclusions from that you like. I try to be an honest and meticulous historian, not a sociologist. 1-55365-049-2

[BCBW 2004] "Geography"

Hayes wins Toronto award

Press Release (2009)

Vancouver, BC - October 19, 2009. Douglas & McIntyre, an imprint of D&M Publishers, is proud to announce that Derek Hayes's book Historical Atlas of Toronto has won the 2009 Heritage Toronto Award in the book category. Heritage Toronto also awards prizes for Architectural Conservation and Craftsmanship, Media, and Community Heritage.

The Historical Atlas of Toronto, now available in paperback (978-1-55365-497-1, $34.95), uses a wealth of beautiful and revelatory maps to create a fascinating visual history of Toronto's development. The Toronto Sun reviewed the book, saying:

"Hayes' new book Historical Atlas of Toronto is a superb collection of rare maps, each of which was prepared to record, promote, define or illustrate an historical event or chapter in the city's growth. There are early street maps, waterfront maps, early housing subdivision maps, transportation route maps and so on. In fact, it's almost impossible to put into words the incredible selection Derek has amassed in his new book. You've got to see the book to believe it!";

Hayes has written twelve books for Douglas & McIntyre (9 of which are part of the Historical Atlas series) and is currently working on Historical Atlas of the North American Railroad (2010) and Historical Atlas of Washington & Oregon (2011).

British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (D&M $59.95)

Article

Derek Hayes' thirteenth large-format atlas, British Columbia: A New Historical Atlas (D&M $59.95), is another labour of love from Hayes-an extraordinarily detailed account of British Columbia history, profusely illustrated-as has become his trademark-with 914 historical maps, all reproduced in original colour, along with 222 old photos and images, and 43 photos he took himself.

It's easy to predict it will become a required reference work, stored on the same shelf as the Encyclopedia of B.C., Chuck Davis' Vancouver volumes, Robin Inglis' Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Coast of America and Jean Barman's West Beyond the West.

In Hayes' words, it's a cornucopia of history-and he hastens to add it's not a new edition of his Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest with which he made his debut in 1999. Only 33 of the maps were in that first atlas. He says 65 per cent of the maps in the new atlas have never been published before.

Highlights include an aboriginal-drawn map, of which there are remarkably few, and a newly discovered bird's-eye map of the entire colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island with so many egregious errors extant as to render it essentially useless for practical purposes, but highly amusing.

**

Hayes traces the complex story of how British Columbia obtained that adjective British, starting with the 1579 voyage of Sir Francis Drake. (There is still no proof that Drake reached British Columbia waters-and it's unlikely he did, according to the Drake Society of California-but we know the Brits and Spanish explored West Coast waters in the late 1700s after a Spaniard named Juan P�rez got here first, in 1774.

Occupation by Britons began in 1805 when the North West Company, following Alexander Mackenzie's 1793 footsteps, crossed the Rockies and began to set up a fur trade network that was taken over by the Hudson's Bay Company in 1821.

In 1799, the Russian American Company had been granted a charter by the tsar that gave it a monopoly of the fur trade and by 1804 it had established a headquarters at Sitka. In 1821 the tsar was persuaded to issue a ukase, or imperial edict, claiming Russian sovereignty south to 51°N which produced formal complaints from both Britain and the United States.

The Russian claim was negotiated back to 54�40�N by treaty with the United States and with Britain the following year. This is today the latitude of the southern extent of the Alaska Panhandle.

Fur traders were the first to make maps of the interior of the province, a number of which are reproduced in Hayes' book. Also shown are various boundary proposals as first Russia and then the United States flexed their muscles.

**

It is difficult to know where to begin to provide a synopsis of an atlas that covers aboriginal settlements, European exploration, fur trading, gold rushes, colonialism, railways, mining, agriculture, forestry and fishing.

Here are ten "stops of interest.";

1. Should we claim Blaine?

Back in 1846, it was agreed our southern boundary would be at 49�N, except for Vancouver Island. British proposals had generally showed a boundary at the Columbia River, which would have placed much of Oregon and all of Washington under the Union Jack. The United States had been posturing for 54�40�N as a northern boundary, which would have completely eliminated a British presence on the West Coast. Even after the 1846 agreement, the San Juan Islands were still in contention. It was not until 1872 that arbitration by the German Kaiser settled the boundary at where it is today. But Hayes tells us the surveying for the 49°N boundary line was incorrectly done. The boundary line for the 49th parallel actually runs through the middle of what is today Blaine, Washington. It took another treaty, in 1908, to agree to leave the boundary not at 49°N but where it was surveyed, about 300m north of that.

2. Murder on the Canadian Pacific

After contractor Andrew Onderdonk imported thousands of Chinese workers for the building of the transcontinental railway in the West, anti-Chinese sentiment was rampant among the European population. One of the worst incidents of violence took place as the track laying approached Lytton. On May 8, 1883 an American foreman, one Mr. Gray, fired two workers he believed were lazy and then refused to pay them for the work they had completed that morning. The rest of the gang then attacked the foreman and three others, injuring one of them.

That night twenty workers, all of them thought to be Americans, stole into the Chinese camp, severely clubbing and beating its inhabitants who tried to escape in the dark. The attackers set fire to the camp. Nine Chinese workers were left on the ground for dead, all with serious head injuries. One labourer, Yee Fook, died on the spot-a severe case, the Daily Colonist in Victoria reported the next week, where "the brain appeared to be oozing from the skull."; An extremely rare map from a private collection shows the location of a hole where the body was found, along with numerous other details that illuminate the way the railways construction gangs worked. The map is thought to have been drawn up as evidence for a trial.

3 The Chilcotin massacre

Hoping to build a railway to the Cariboo gold fields, Alfred Waddington began construction for a wagon road that would connect Vancouver Island to the mainland by island hopping and following Bute Inlet towards the interior. Hungry Tsilhqot'in (then known as Chilcotin), angered and frightened by deaths from smallpox, demanded food from a ferryman on the Homathko River and killed him when he refused, on April 29, 1864. Provisions intended for the construction works were taken. The next morning the Tsilhqot'in fell on the construction camp at dawn, killing nine workers; three escaped. Then they located William Brewster, the foreman, and three others farther up the trail and killed them too. Later they ambushed a pack train and killed more people.

Fearing a general uprising, Governor Frederick Seymour organized two parties to track down the killers. William Cox, a gold commissioner, made contact and persuaded the Tsilhqot'in leaders to surrender. The chiefs thought they had been given immunity, but they had not; Chief Klatsassin and four other chiefs were arrested and in September 1864 tried by Judge Begbie at Quesnelmouth (Quesnel). They were found guilty and hanged. Chief Klatsassin, in his defence, said that the Tsilhqot'in had been waging war, not committing murder. A map was drawn up at the time showing the locations of the surrender and various killings. The map is thought to have been produced for the information of the authorities as they pondered a course of action.

4. Baillie-Grohman's dream

In 1882 William Adolph Baillie-Grohman, a British sportsman and author, embarked on a fantastic project. He proposed to link the Upper Columbia River at its source - Columbia Lake - with the Kootenay River, in order to lower the level of Kootenay Lake, a considerable distance downstream on the Kootenay River, so that he could reclaim flat land that flooded every year at the southern end of the lake. It was a grandiose project that would make today's environmentalists throw up their hands in despair, but in the freewheeling 1880s no one seemed to disapprove.

By 1889, employing mainly Chinese labour, Baillie-Grohman constructed a canal linking the Columbia and the Kootenay at Canal Flats, enabling Baillie-Grohman to claim a large land grant. He even began the first steamboat service on the Upper Columbia (brilliantly circumventing customs duties payable on a boat imported from the United States by declaring it was an agricultural implement, meant to pull a steam plow on the lands he was to reclaim). It takes a map to fully appreciate the visionary scope of Baillie-Grohman's land reclamation and development dream; Hayes's book contains one published to convince investors to chance their money in the scheme.

5. Steamboats and fruit

The valleys of the interior generally run north to south and some contain lakes, and this allowed relatively easy connection to the Canadian Pacific Railway by other railways and steamboats plying the long lakes. Beginning in 1886, steamboats on Okanagan Lake began to service new lake settlements such as Penticton and Kelowna. Canadian Pacific had a transportation monopoly for many years until a railway built by Canadian National to Kelowna broke the Okanagan monopoly in 1925.

Steamboats and railways permitted the agricultural development of the Okanagan Valley, enhanced by irrigation, because fruit growers could have their produce quickly shipped to market. The atlas shows maps of rail lines that connect with the CPR, maps of steamboat routes on Okanagan Lake, the Arrow Lakes, and others, and also reproduces promotional maps for irrigated agricultural land and the creation of townsites such as Kaleden, Summerland and Naramata.

6. Railways Abound

Rail lines were proposed for nearly every corner of the province near the outset of the 20th century. Many failed. The Pacific Great Eastern ran out of money north of Quesnel and was taken over by the provincial government. For decades this railway ran "from nowhere to nowhere"; until a connection was made between Vancouver and Prince George in 1956.

Built by the Canadian Pacific as the Kettle Valley Railway, a difficult Coast-to-Kootenay railway was constructed to prevent inroads by American railways across the border which offered much easier routes. There are planning and operating maps of both the Pacific Great Eastern Railway and the Kettle Valley Railway in the atlas, and also a summary map of all the lines proposed and under construction in 1912.

7. Boom and bust in real estate

British Columbia was thought to have a boundless future following the opening of the Panama Canal. In his previous Historical Atlas of Vancouver, Hayes included maps from real estate ads just before World War I when real estate speculation was rampant. The war abruptly squelched speculators and by 1916 land that had sold for hundreds of dollars was being sold for taxes, with few takers.

Hayes has uncovered more real estate maps from 1907-1914. Although some parts of Vancouver owe their beginnings in this period, many more proposed schemes didn't get off the ground until very much later. When the end was in sight for land-grabbing opportunists, one magazine even offered free lots in White Rock with a subscription, and no, that's not a misprint: a lot free with a magazine subscription!

8. Canberra North

Charles Melville Hays has been in the news this year with the centenary of his death aboard the ill-fated Titanic. Until 1912, Hays was general manager of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway which brought immense changes to northern B.C., including the creation of Prince Rupert and Prince George. The former was intended to be the Pacific terminus of a new transcontinental line, the latter would be part of the railway's speculative land development plan. Hayes's book reproduces the original plans for both model towns, as well as Vanderhoof.

Booster magazine Canada West publisher and railway publicist Herbert Vanderhoof wanted his namesake town to be something special-a literary centre, believe it or not-so he hired Walter Burley Griffin and Francis Barry Byrne, both "flat roof"; Prairie School architects who had apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright, to produce a plan. Their layout, with curved streets conforming to the topography (rather than the grid pattern then the norm) was to include civic buildings and tree-lined avenues along the lines of another city Griffin was responsible for-Canberra, the new federal capital of Australia. Griffin's Vanderhoof plan can be found in Hayes' atlas.

9. Rules of the roads

Hazelton ran a competition in 1911 to reward the first car to reach their new town. The winner arrived by driving along river beds and, it was later revealed, dismantling his car and packing the parts over trails, reassembling the vehicle when Hazelton was close by. Hayes's atlas depicts a 1919 tourist road map complete with the banner admonition "The Rule of the Road in British Columbia - Keep to the Left."; He also reproduces a map that documents the changeover from left to right which began the following year.

The majority of the province outside of Vancouver Island and the southwestern mainland changed from left hand driving to right hand driving as of January 1, 1920. It was easy for them; there were few roads with more than a single lane. The rest of the province changed two years later. A two-stage change was possible because the two parts of the province were not connected by road. Construction of the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway (now Canadian National) in the Fraser Canyon had obliterated the road in many places. The Hope-Princeton highway was not completed until 1949. Maps indicated the necessity of shipping cars between Hope and Princeton by rail.

10. Defending the coast

Long before Pearl Harbor the Canadian military had been preparing for a possible attack by the Japanese from the sea, an anticipation that came to a head in the months following Pearl Harbor when an oil refinery near Los Angeles was shelled by a submarine, and air attacks were thought to have occurred; in June came the reported attack on Estevan Lighthouse, on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Shortly after the United States ordered all persons of Japanese descent removed from the coast, Canada did the same. Hayes's book shows maps of some of the detention camps set up in the interior to house them, maps drawn by internees themselves. As with many of the maps in the book, they are combined with old and modern photos to better convey what they were like.

Declassified military maps in the atlas indicate gun batteries in Vancouver at Point Grey, Point Atkinson, and Stanley Park, guarding Vancouver Harbour, and Steveston, guarding the mouth of the Fraser; on Albert Head, guarding Esquimalt Harbour; and at the entrance to Prince Rupert Harbour. Yorke Island, near Kelsey Bay, was fortified with long-range guns to guard the northern entrance to the Strait of Georgia. To guard the Skeena Valley east of Prince Rupert, Canada's only armoured train ran secretively back and forth. The atlas shows a map published in an American newspaper in 1943 that purported to have been captured from a Korean spy and showed the Japanese invasion plans for the entire west coast of North America.

978-1-92681-257-1

[BCBW 2012]

Canada: An Illustrated History by Derek Hayes (D&M $36.95)

Article (2016)

No matter how you vote, you have to admit the notion that Canada is a construct worth preserving has been reinvigorated with the election of Trudeau the Younger. Just that decision to stop slowly starving the CBC to death is enough to make millions believe we are no longer inexorably destined to emulate the catastrophic capitalist spiral of our neighbour to the south.

It's therefore good timing for Derek Hayes' revised and expanded, Canada: An Illustrated History to coincide with the country's 150th anniversary in 2017.

Without a great deal of chest-thumping, the multi-award winning geographer Hayes has fashioned a marvelous tour of our national story, from explorer Jacques Cartier to astronaut Chris Hadfield.

B.C. doesn't get short shrift. We get Wreck Beach hippies, Terry Fox, Justin at Vancouver's Pride Parade and two pages devoted to the iconic photo taken by Claude Detloff in New Westminster on October 1, 1940.

When members of the B.C. Regiment of the Duke of Connaught's Own Rifles were marching to the railway station and overseas for WW II, a boy named Warren Bernard ran after his father Jack Bernard and reached out his little hand.

It was a great image to stoke the flames of patriotism. But Hayes reveals the facts. Jack Bernard was marching off to war against the wishes of his young wife. Their marriage disintegrated. He survived the war and died in 1981.

The photo known as "Wait for Me, Daddy"; inspired a memorial statue at the foot of Eighth Street that was unveiled in 2014 with Warren 'Whitey' Bernard-the 79-years-young boy who appeared in the photo-in attendance.

978-1-77162-120-5

BCBW (Winter 2016)

Home

Home