Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth

by Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, and Willard Joseph

Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2017

$40.00 (U.S.) / 9780803296923

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

Imagine a blanket spread out on a table. It is a Salish blanket, over a hundred years old, humble, plain, tan-coloured, with a dark brown stripe at each end. Worn and frayed, it does not look exceptional, yet a group of six women and men surround it in reverence. They are Squamish (Puget Sound Salish) First Nation singers and weavers. They are singing an honour song to welcome the blanket back – back from the obscurity of a storeroom of the Burke Museum in Seattle. The sight and sound sends chills up the spines of the people watching, a large gathering of some 100 people. One weaver gently places her hands lovingly on the blanket. They are shaking with emotion. Another woman gives a prayer of thanks to the blanket.

This was when I realized that Coast Salish blankets have a life of their own, that they command respect and reverence for these are animate objects, breathing history, stories, knowledge, lessons, and spirituality. They are alive with beings, alive with a heartbeat of their own. To view them with any degree of understanding, and to appreciate their importance, we need to acquire an informed perspective, one that places them in their context, in their functional role, and within their culture.

Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth does just that. The first paragraph, by Chief Janice George of Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish), helps jolt you into that perspective: “You should think about blankets as merged objects. They are alive because they exist in the spirit world. They are the animal. They are part of the hunter; they are part of the weaver; they are part of the wearer.”

Salish Blankets helps to address a long interlude between books about Coast Salish blankets. The last major book, Salish Weaving by Paula Gustafson, was published almost forty years ago (Douglas & McIntyre, 1980), and is now out of print. In those four decades the world of Salish blankets has expanded and developed a great deal, thanks in part to the revival of and interest in Salish weaving. This book comes just as UBC’s Museum of Anthropology held a highly successful exhibit of Salish blankets, “Fabric of our Land,” featuring ten blankets from the 1800s loaned from museums around the world, which were displayed along with over two dozen modern Salish weavings.

This timely book will go a long way to satisfy the desire generated from that exhibit for more information on the subject. Salish Blankets also contributes enormously to a growing awareness of previously unrecognized and under-reported women’s arts, especially Indigenous women’s arts. Somehow Coast Salish blankets, despite embodying complex knowledge of fibres and outstanding skill in spinning, design, and weaving, have remained relatively unknown. Salish Blankets aims to change this by highlighting and explaining the exquisiteness and importance of these blankets.

The authors, Leslie Tepper, Janice George (Chepximiya Siyam), and Willard (Buddy) Joseph (Skwetsimltexw), are well versed in the subject and bring a range of valuable perspectives. Tepper, who recently retired as Curator of Western Ethnology at the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa, has worked closely with First Nations, particularly in the area of Indigenous textiles. Her curator’s perspective provides an appreciation of the stories embedded in objects, along with well-researched history and an accessible academic approach.

Tepper and George, who is a Squamish hereditary chief, travelled to many countries to visit museums housing Salish blankets, spent countless hours analyzing them, and together developed resources that have helped revive Salish weaving.

Janice George and Buddy Joseph, who is also Squamish, come from a long line of Salish weavers, and the two have worked together for many years to revitalize the skills of weaving. When they started in 2004, only one weaver remained in the Squamish community of Squamish. Since then, Janice George and Buddy Joseph have taught over 2,500 weavers.

Along with the 1960s and 70s weaving revival of the Sto:lo Nation, and the 1980s revival of Musqueam weavers, the role of George and Joseph has been inspirational, and their contribution to the Salish weaving revival has been incalculable. Along with their technical weaving knowledge, they bring to Salish Blankets a deep understanding of the spiritual and cultural aspects of Salish weaving and Salish blankets. This ancestral and spiritual knowledge makes the book stand out from anything written before on the subject.

A fundamental concept they want to incorporate is the idea that blankets are “worn for spiritual protection.” They achieve this with notable success. Woven throughout the book are many examples of how the blankets are used in ceremonies to provide the reader with a clearer understanding of the blankets’ significance and role.

Salish Blankets starts with an overview of tools, techniques, and background, and how we know what we do about the history of these blankets. Readers will learn about life event ceremonies in which blankets play a role, including baby welcomings, puberty rituals, namings, weddings, funerals, and memorials; the role of speakers and witnesses; and the use of weavings in ceremonial settings.

As the authors point out, museum objects simply do not convey the “strong emotions and impressive events of their ceremonial context.” The book helps make that connection. Two chapters delve into details about the blanket and tumpline weavings — colour, design, motifs, and categories of blanket styles.

While Salish Blankets contains many helpful photographs and diagrams, readers would benefit if the book had featured, early on in the book, comparative illustrations of the various design categories, e.g., Fuca, Capilano, classic, double layered/disorganized, etc.

Later on, a selection of five blankets pulls these aspects together to provide greater detailed analysis. While these details might be of moderate interest to the casual reader, they will be of intense interest to weavers and scholars of Salish blankets.

The authors contribute an important and fresh perspective on a category they term “double-layered” blankets, previously described somewhat negatively as “disorganized” blankets. This explanation casts a whole new light on this style of blanket, and I found myself jolted into a new way of admiring the impressive skill of the weaver. Once pointed out, I wondered how I and other researchers had overlooked this perspective!

The last chapter brings in a different voice, that of Squamish weaver Joy Joseph-McCullough (Siyaltemaat), who sees the art of weaving as the “heartbeat of our nation,” a process that brings in the ancestors to guide the teachings. She also emphasizes another role of Salish blankets, that of education: teaching the general public not only about weaving as an art form, but as an acknowledgement of Salish culture.

One of the book’s notable strengths lies in Appendix 1 (“Teachings and Stories”), a collection of teachings from the Squamish culture. Perhaps the teachings would serve better if embedded into the chapters, so as to not be overlooked. Yet seen all together in one place, they do serve to concentrate the blankets’ important instructional and pedagogical role. In any event, readers should make sure to spend time in this appendix.

Salish Blankets does overlook a few elements. I would have appreciated more information about the fibres and spinning, and discussion of Salish blankets that recent research has shown contribute additional interesting details.

However, this lack does not diminish the value of the book. Missing elements reflect the scarcity of researchers in the field, the relative obscurity of the subject of Salish textiles, and the increasing and hard-to-keep-up-with Salish blanket studies. I hope this book inspires more interest in documenting these blankets.

The book will appeal to any and all readers seeking knowledge about the Coast Salish cultures — from community members to scholars. It will be especially relevant for those interested in textiles and, of course, it will be vital to weavers of Salish blankets themselves.

“The object, the maker, the wearer, and the community itself are bound and transformed through the creation and use of the Salish blanket,” note Tepper, George, and Joseph in their introduction.

I might add that Salish Blankets will transform how you see these blankets — not as static museum objects but as a living tradition that is part of the hunter, part of the weaver, and part of the wearer in Salish culture.

*

Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, who retired recently as Director of Research Services at Vancouver Island University, holds a Master Spinners Certificate and completed a research project focusing on the Coast Salish spinning of traditional fibres into yarns. She has researched Coast Salish textiles in museum collections including the Royal British Columbia Museum, the UBC Museum of Anthropology, the Canadian Museum of History, the Perth Museum, the British Museum, the Pitt Rivers Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Burke Museum in Seattle. She has given presentations at Coast Salish weaving workshops and for the Textile Society of America, and has written about the use of diatomaceous earth in Salish blankets (see “A Curious Clay: The Use of Powdered White Substance in Coast Salish Spinning and Woven Blankets,” BC Studies 189 (Spring 2016), pp. 129-150). Liz was also instrumental in identifying the only blanket in a Pacific Coast museum now known to be made of Salish woolly dog hair. Liz is honoured to have had the privilege to paddle over 1,000 miles along the coast from Olympia to Bella Bella with First Nations on five Tribal Journeys. She is grateful for the knowledge shared with her by Indigenous weavers and spinners. She lives and spins on Protection Island.

*

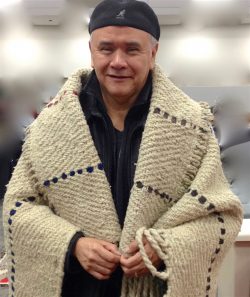

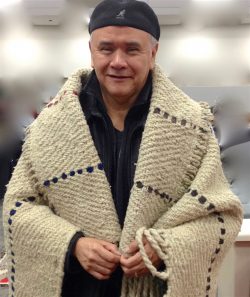

PHOTOS: Janice George; Buddy Joseph.

ILMBC2

by Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, and Willard Joseph

Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2017

$40.00 (U.S.) / 9780803296923

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

Imagine a blanket spread out on a table. It is a Salish blanket, over a hundred years old, humble, plain, tan-coloured, with a dark brown stripe at each end. Worn and frayed, it does not look exceptional, yet a group of six women and men surround it in reverence. They are Squamish (Puget Sound Salish) First Nation singers and weavers. They are singing an honour song to welcome the blanket back – back from the obscurity of a storeroom of the Burke Museum in Seattle. The sight and sound sends chills up the spines of the people watching, a large gathering of some 100 people. One weaver gently places her hands lovingly on the blanket. They are shaking with emotion. Another woman gives a prayer of thanks to the blanket.

This was when I realized that Coast Salish blankets have a life of their own, that they command respect and reverence for these are animate objects, breathing history, stories, knowledge, lessons, and spirituality. They are alive with beings, alive with a heartbeat of their own. To view them with any degree of understanding, and to appreciate their importance, we need to acquire an informed perspective, one that places them in their context, in their functional role, and within their culture.

Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth does just that. The first paragraph, by Chief Janice George of Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish), helps jolt you into that perspective: “You should think about blankets as merged objects. They are alive because they exist in the spirit world. They are the animal. They are part of the hunter; they are part of the weaver; they are part of the wearer.”

Salish Blankets helps to address a long interlude between books about Coast Salish blankets. The last major book, Salish Weaving by Paula Gustafson, was published almost forty years ago (Douglas & McIntyre, 1980), and is now out of print. In those four decades the world of Salish blankets has expanded and developed a great deal, thanks in part to the revival of and interest in Salish weaving. This book comes just as UBC’s Museum of Anthropology held a highly successful exhibit of Salish blankets, “Fabric of our Land,” featuring ten blankets from the 1800s loaned from museums around the world, which were displayed along with over two dozen modern Salish weavings.

This timely book will go a long way to satisfy the desire generated from that exhibit for more information on the subject. Salish Blankets also contributes enormously to a growing awareness of previously unrecognized and under-reported women’s arts, especially Indigenous women’s arts. Somehow Coast Salish blankets, despite embodying complex knowledge of fibres and outstanding skill in spinning, design, and weaving, have remained relatively unknown. Salish Blankets aims to change this by highlighting and explaining the exquisiteness and importance of these blankets.

The authors, Leslie Tepper, Janice George (Chepximiya Siyam), and Willard (Buddy) Joseph (Skwetsimltexw), are well versed in the subject and bring a range of valuable perspectives. Tepper, who recently retired as Curator of Western Ethnology at the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa, has worked closely with First Nations, particularly in the area of Indigenous textiles. Her curator’s perspective provides an appreciation of the stories embedded in objects, along with well-researched history and an accessible academic approach.

Tepper and George, who is a Squamish hereditary chief, travelled to many countries to visit museums housing Salish blankets, spent countless hours analyzing them, and together developed resources that have helped revive Salish weaving.

Janice George and Buddy Joseph, who is also Squamish, come from a long line of Salish weavers, and the two have worked together for many years to revitalize the skills of weaving. When they started in 2004, only one weaver remained in the Squamish community of Squamish. Since then, Janice George and Buddy Joseph have taught over 2,500 weavers.

Along with the 1960s and 70s weaving revival of the Sto:lo Nation, and the 1980s revival of Musqueam weavers, the role of George and Joseph has been inspirational, and their contribution to the Salish weaving revival has been incalculable. Along with their technical weaving knowledge, they bring to Salish Blankets a deep understanding of the spiritual and cultural aspects of Salish weaving and Salish blankets. This ancestral and spiritual knowledge makes the book stand out from anything written before on the subject.

A fundamental concept they want to incorporate is the idea that blankets are “worn for spiritual protection.” They achieve this with notable success. Woven throughout the book are many examples of how the blankets are used in ceremonies to provide the reader with a clearer understanding of the blankets’ significance and role.

Salish Blankets starts with an overview of tools, techniques, and background, and how we know what we do about the history of these blankets. Readers will learn about life event ceremonies in which blankets play a role, including baby welcomings, puberty rituals, namings, weddings, funerals, and memorials; the role of speakers and witnesses; and the use of weavings in ceremonial settings.

As the authors point out, museum objects simply do not convey the “strong emotions and impressive events of their ceremonial context.” The book helps make that connection. Two chapters delve into details about the blanket and tumpline weavings — colour, design, motifs, and categories of blanket styles.

While Salish Blankets contains many helpful photographs and diagrams, readers would benefit if the book had featured, early on in the book, comparative illustrations of the various design categories, e.g., Fuca, Capilano, classic, double layered/disorganized, etc.

Later on, a selection of five blankets pulls these aspects together to provide greater detailed analysis. While these details might be of moderate interest to the casual reader, they will be of intense interest to weavers and scholars of Salish blankets.

The authors contribute an important and fresh perspective on a category they term “double-layered” blankets, previously described somewhat negatively as “disorganized” blankets. This explanation casts a whole new light on this style of blanket, and I found myself jolted into a new way of admiring the impressive skill of the weaver. Once pointed out, I wondered how I and other researchers had overlooked this perspective!

The last chapter brings in a different voice, that of Squamish weaver Joy Joseph-McCullough (Siyaltemaat), who sees the art of weaving as the “heartbeat of our nation,” a process that brings in the ancestors to guide the teachings. She also emphasizes another role of Salish blankets, that of education: teaching the general public not only about weaving as an art form, but as an acknowledgement of Salish culture.

One of the book’s notable strengths lies in Appendix 1 (“Teachings and Stories”), a collection of teachings from the Squamish culture. Perhaps the teachings would serve better if embedded into the chapters, so as to not be overlooked. Yet seen all together in one place, they do serve to concentrate the blankets’ important instructional and pedagogical role. In any event, readers should make sure to spend time in this appendix.

Salish Blankets does overlook a few elements. I would have appreciated more information about the fibres and spinning, and discussion of Salish blankets that recent research has shown contribute additional interesting details.

However, this lack does not diminish the value of the book. Missing elements reflect the scarcity of researchers in the field, the relative obscurity of the subject of Salish textiles, and the increasing and hard-to-keep-up-with Salish blanket studies. I hope this book inspires more interest in documenting these blankets.

The book will appeal to any and all readers seeking knowledge about the Coast Salish cultures — from community members to scholars. It will be especially relevant for those interested in textiles and, of course, it will be vital to weavers of Salish blankets themselves.

“The object, the maker, the wearer, and the community itself are bound and transformed through the creation and use of the Salish blanket,” note Tepper, George, and Joseph in their introduction.

I might add that Salish Blankets will transform how you see these blankets — not as static museum objects but as a living tradition that is part of the hunter, part of the weaver, and part of the wearer in Salish culture.

*

Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, who retired recently as Director of Research Services at Vancouver Island University, holds a Master Spinners Certificate and completed a research project focusing on the Coast Salish spinning of traditional fibres into yarns. She has researched Coast Salish textiles in museum collections including the Royal British Columbia Museum, the UBC Museum of Anthropology, the Canadian Museum of History, the Perth Museum, the British Museum, the Pitt Rivers Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Burke Museum in Seattle. She has given presentations at Coast Salish weaving workshops and for the Textile Society of America, and has written about the use of diatomaceous earth in Salish blankets (see “A Curious Clay: The Use of Powdered White Substance in Coast Salish Spinning and Woven Blankets,” BC Studies 189 (Spring 2016), pp. 129-150). Liz was also instrumental in identifying the only blanket in a Pacific Coast museum now known to be made of Salish woolly dog hair. Liz is honoured to have had the privilege to paddle over 1,000 miles along the coast from Olympia to Bella Bella with First Nations on five Tribal Journeys. She is grateful for the knowledge shared with her by Indigenous weavers and spinners. She lives and spins on Protection Island.

*

PHOTOS: Janice George; Buddy Joseph.

ILMBC2

Home

Home