Prairie-born (1955) Métis/Icelandic Jónína Kirton has been much concerned with equity and inclusion. She coordinated the first National Indigenous Writers Conference in Vancouver in 2013. She is a graduate of Simon Fraser's Writers Studio (2007) and a recipient of the Emerging Aboriginal Writer's Residency at the Banff Centre (2008). In 2016 she accepted the 2016 Mayor's Arts Award for Emerging Artist in the Literary Arts category, as selected by Betsy Warland, former director of the SFU's Writers Studio.

Kirton has been active within the Aboriginal Writers Collective on the West Coast. Loosely autobiographical, Kirton's first book of poetry, "page as bone - ink as blood" (Talonbooks, 2015) is a memoir in verse that bridges Kirton's European and First Nation cultures. She uses poignant images and stories of the senses to explore family secrets, black holes of trauma, and retrieved memories. "What our minds have forgotten or locked away," she has written, "the body never forgets."

Kirton's writing has appeared in anthologies and literary journals including Ricepaper, V6A: Writing from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speak Out, Pagan Edge, First Nations Drum, Toronto Quarterly and Quills Canadian Poetry Magazine. She won first prize and two honourable mentions in the 2013 Royal City Literary Arts Society's Write On Contest. Kirton was also a finalist in the 2013 Burnaby Writers' Society Writing Contest.

BOOKS:

page as bone - ink as blood (Talonbooks, 2015) $16.95 9780889229235

An Honest Woman (Talonbooks, 2017) $16.95 9781772011449

Standing in a River of Time (Talonbooks, 2022) $19.95 9781772013795

[BCBW 2022]

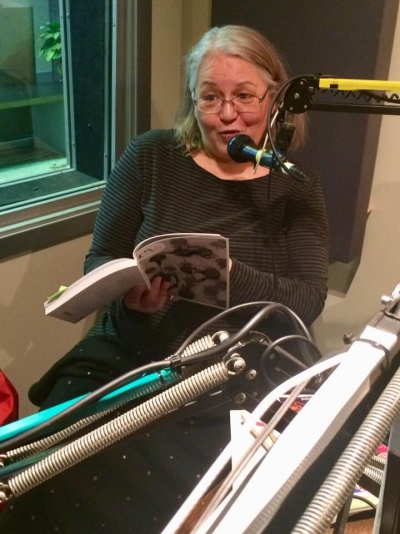

At the Native Education Centre. Photo by Tim Matheson

Standing in a River of Time

by Jónína Kirton (Talonbooks $ 19.95)

Interview by Beverly Cramp

rowing up with a violent, alcoholic father and losing two of her three brothers at an early age, Jónína Kirton experienced trauma. She also turned to alcohol as a young woman before beginning a lifetime of spiritual healing and sobriety. Kirton is remarkably honest about the hard realities of her life and the people who came to her aid in Standing in a River of Time. Kirton began writing poetry, and in 2016, received a City of Vancouver Mayor’s Arts Award for an Emerging Artist. Her second collection of poetry, An Honest Woman (Talonbooks, 2017) was a finalist for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize.

BC BookWorld: You start your memoir as your mother is dying. Was that the most trying period in your life?

Jónína Kirton: I would not describe her dying as a trying time. It was more of an awakening. As the only girl, I was very close to my mother, a beautiful woman, that I jokingly referred to as the “church lady” due to her devotion to her faith. She was a kind woman, interested in community and always learning. The way she negotiated her final days, still thinking of others and caring for her family, made me realize how selfish and self-centred I had become. Unhealed people can be very self-centred. They can’t help it. They walk around with open wounds, thin skin, that is easily hurt. It is hard to think of others when you are in that kind of pain, and yet my mother managed to do this. Seeing this and witnessing the miracle of her leaving her body sent me even deeper into my own healing.

BCBW: Your father’s troubled identity as a Métis man who is an alcoholic caused problems in your family. Later in life you learned that racism and colonialism were to blame for many of his destructive behaviours. Do you think he ever realized that?

JK: Despite a few attempts, one that included Antabuse, he was never able to stop drinking. Drinking led to violence, to overspending and to things like drunk driving charges. So even though my father was successful in his career and well respected by many, he lived his entire adult life in that downward shame spiral that comes with alcoholism. Not one to talk about himself, most of what I know about my father came from my mother and other family members. I was a teenager questioning our ancestry when my mother told me, “Your father hates being Native.” I was told to not talk to him about it, but later in life, as I uncovered the rich history of our Métis ancestors, I decided to share the stories with him. At first, he was resistant, but years later, around the time the Truth and Reconciliation Committee was in the news, he became more open. He never spoke about this to me, but I feel that between the TRC and what I shared with him he did make peace with being Indigenous. I like to think that he began to feel some pride, as shortly before his death in 2017, he told me that he wanted to get his Métis citizenship. This after a lifetime of denying he was Indigenous. No matter what happened between us, I have always loved him. He is my dad. Not only did he and my mother give me life, I also know he tried really hard to give us kids a good life. He deserves to be at peace.

BCBW: When did you embrace your Métis heritage?

JK: I always knew that I was what we called “part-Native” but didn’t know I was Métis until my forties when my cousin, an enumerator for Saskatchewan Métis, offered to confirm this. I literally fell to my knees and wept when I received the genealogy report she had put together for me. All those years of being told to not talk about our Indigenous ancestry melted away. I finally felt free.

BCBW: You also pay attention to your Icelandic heritage (on your mother’s side). How has this been a source of strength for you?

JK: I end the book with a quote from my Icelandic grandmother whose name I carry. I do this because I wanted to show that Icelanders also care for this earth, and show the pride I feel about being her grandchild and being Icelandic. Grandmother was a strong woman, the mother of seventeen children, all home births. She was a joyful woman and never complained, despite living in poverty. Having her name is an honour. My Icelandic aunts and uncles embody her strength, strength that I did not fully understand until I went to Iceland in 2017. While there I saw the beauty and yet harshness of those lands. I saw what it must have taken to live there in the early days. I saw their love of story and poetry and realized that I get my desire to tell stories from both sides.

BCBW: In your book’s foreword, Wanda John-Kehewin writes “Loss and love run through this work, which is about acceptance and healing through truth.” Was detailing the healing power of truth the major aim of this book? Or did writing your memoir bring out your story of healing?

JK: There has been something very healing about documenting some of the harm I have experienced. There can be no reconciliation without truth. Abusers rarely admit to what they have done and often use gaslighting to keep you questioning reality. Truth becomes muddy, and I like clarity. In fact, when referring to my second book, An Honest Woman, Betsy Warland said, “Kirton picks over how she was raised familially and culturally like a crime scene.” Her assessment was accurate, and I was tickled. Writing that book I was on a mission to expose the world that young women and girls enter. When writing, Standing in a River of Time, I felt, in fairness, that I needed to soften my gaze and share hard truths about some of the things I had done.

The title, Standing in a River of Time, comes from a teaching I once heard about time being a river with the future at our back moving towards us and the past in front of us flowing away. I used this title as I do believe that unless one has the gift of prophesy, we can’t see the future, but we can examine the past and in doing so we can make peace with things that have caused us pain. What I hoped to convey in the book was that the healing may never be done and that this is okay. The book was never intended to be a road map for healing but rather to show how messy healing can be and that accepting our imperfections could bring much needed change in the

world. 9781772013795

Beverly Cramp is publisher of BC BookWorld.

[BCBW 2022]

Kirton has been active within the Aboriginal Writers Collective on the West Coast. Loosely autobiographical, Kirton's first book of poetry, "page as bone - ink as blood" (Talonbooks, 2015) is a memoir in verse that bridges Kirton's European and First Nation cultures. She uses poignant images and stories of the senses to explore family secrets, black holes of trauma, and retrieved memories. "What our minds have forgotten or locked away," she has written, "the body never forgets."

Kirton's writing has appeared in anthologies and literary journals including Ricepaper, V6A: Writing from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speak Out, Pagan Edge, First Nations Drum, Toronto Quarterly and Quills Canadian Poetry Magazine. She won first prize and two honourable mentions in the 2013 Royal City Literary Arts Society's Write On Contest. Kirton was also a finalist in the 2013 Burnaby Writers' Society Writing Contest.

BOOKS:

page as bone - ink as blood (Talonbooks, 2015) $16.95 9780889229235

An Honest Woman (Talonbooks, 2017) $16.95 9781772011449

Standing in a River of Time (Talonbooks, 2022) $19.95 9781772013795

[BCBW 2022]

At the Native Education Centre. Photo by Tim Matheson

Standing in a River of Time

by Jónína Kirton (Talonbooks $ 19.95)

Interview by Beverly Cramp

rowing up with a violent, alcoholic father and losing two of her three brothers at an early age, Jónína Kirton experienced trauma. She also turned to alcohol as a young woman before beginning a lifetime of spiritual healing and sobriety. Kirton is remarkably honest about the hard realities of her life and the people who came to her aid in Standing in a River of Time. Kirton began writing poetry, and in 2016, received a City of Vancouver Mayor’s Arts Award for an Emerging Artist. Her second collection of poetry, An Honest Woman (Talonbooks, 2017) was a finalist for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize.

BC BookWorld: You start your memoir as your mother is dying. Was that the most trying period in your life?

Jónína Kirton: I would not describe her dying as a trying time. It was more of an awakening. As the only girl, I was very close to my mother, a beautiful woman, that I jokingly referred to as the “church lady” due to her devotion to her faith. She was a kind woman, interested in community and always learning. The way she negotiated her final days, still thinking of others and caring for her family, made me realize how selfish and self-centred I had become. Unhealed people can be very self-centred. They can’t help it. They walk around with open wounds, thin skin, that is easily hurt. It is hard to think of others when you are in that kind of pain, and yet my mother managed to do this. Seeing this and witnessing the miracle of her leaving her body sent me even deeper into my own healing.

BCBW: Your father’s troubled identity as a Métis man who is an alcoholic caused problems in your family. Later in life you learned that racism and colonialism were to blame for many of his destructive behaviours. Do you think he ever realized that?

JK: Despite a few attempts, one that included Antabuse, he was never able to stop drinking. Drinking led to violence, to overspending and to things like drunk driving charges. So even though my father was successful in his career and well respected by many, he lived his entire adult life in that downward shame spiral that comes with alcoholism. Not one to talk about himself, most of what I know about my father came from my mother and other family members. I was a teenager questioning our ancestry when my mother told me, “Your father hates being Native.” I was told to not talk to him about it, but later in life, as I uncovered the rich history of our Métis ancestors, I decided to share the stories with him. At first, he was resistant, but years later, around the time the Truth and Reconciliation Committee was in the news, he became more open. He never spoke about this to me, but I feel that between the TRC and what I shared with him he did make peace with being Indigenous. I like to think that he began to feel some pride, as shortly before his death in 2017, he told me that he wanted to get his Métis citizenship. This after a lifetime of denying he was Indigenous. No matter what happened between us, I have always loved him. He is my dad. Not only did he and my mother give me life, I also know he tried really hard to give us kids a good life. He deserves to be at peace.

BCBW: When did you embrace your Métis heritage?

JK: I always knew that I was what we called “part-Native” but didn’t know I was Métis until my forties when my cousin, an enumerator for Saskatchewan Métis, offered to confirm this. I literally fell to my knees and wept when I received the genealogy report she had put together for me. All those years of being told to not talk about our Indigenous ancestry melted away. I finally felt free.

BCBW: You also pay attention to your Icelandic heritage (on your mother’s side). How has this been a source of strength for you?

JK: I end the book with a quote from my Icelandic grandmother whose name I carry. I do this because I wanted to show that Icelanders also care for this earth, and show the pride I feel about being her grandchild and being Icelandic. Grandmother was a strong woman, the mother of seventeen children, all home births. She was a joyful woman and never complained, despite living in poverty. Having her name is an honour. My Icelandic aunts and uncles embody her strength, strength that I did not fully understand until I went to Iceland in 2017. While there I saw the beauty and yet harshness of those lands. I saw what it must have taken to live there in the early days. I saw their love of story and poetry and realized that I get my desire to tell stories from both sides.

BCBW: In your book’s foreword, Wanda John-Kehewin writes “Loss and love run through this work, which is about acceptance and healing through truth.” Was detailing the healing power of truth the major aim of this book? Or did writing your memoir bring out your story of healing?

JK: There has been something very healing about documenting some of the harm I have experienced. There can be no reconciliation without truth. Abusers rarely admit to what they have done and often use gaslighting to keep you questioning reality. Truth becomes muddy, and I like clarity. In fact, when referring to my second book, An Honest Woman, Betsy Warland said, “Kirton picks over how she was raised familially and culturally like a crime scene.” Her assessment was accurate, and I was tickled. Writing that book I was on a mission to expose the world that young women and girls enter. When writing, Standing in a River of Time, I felt, in fairness, that I needed to soften my gaze and share hard truths about some of the things I had done.

The title, Standing in a River of Time, comes from a teaching I once heard about time being a river with the future at our back moving towards us and the past in front of us flowing away. I used this title as I do believe that unless one has the gift of prophesy, we can’t see the future, but we can examine the past and in doing so we can make peace with things that have caused us pain. What I hoped to convey in the book was that the healing may never be done and that this is okay. The book was never intended to be a road map for healing but rather to show how messy healing can be and that accepting our imperfections could bring much needed change in the

world. 9781772013795

Beverly Cramp is publisher of BC BookWorld.

[BCBW 2022]

Home

Home