Ruby Peter was a Cowichan elder and linguist who trained Hul'qumin'um' language teachers and researchers for over six decades. In 2019, she was awarded honorary doctorate degrees by the University of Victoria and Simon Fraser University. She died on January 8, 2021. With more than 4,900 members, the Cowichan people are self-described as the largest First Nation Band in B.C.

BOOKS

Hukari, Thomas E. & Ruby Peter (editors). The Cowichan Dictionary of the Hul'qumin'um' Dialect of the Coast Salish People (Duncan: Cowichan Tribes, 1995).

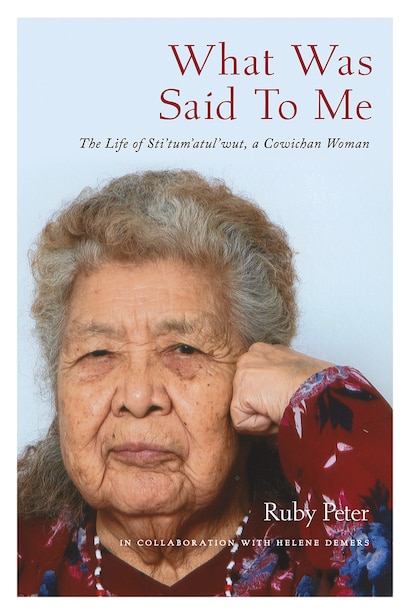

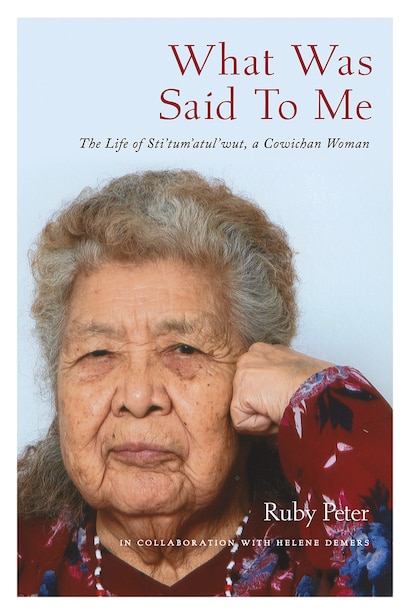

What Was Said to Me: The Life of Sti'tum'atul'wut, a Cowichan Woman. In collaboration with Helene Demers. (Royal BC Museum, 2021) $24.95 9780772679383

[BCBW 2021]

+++

REVIEW 2021

by Latash-Maurice Nahanee

A life well-lived is captured in Sti'tum'atul'wut's (Ruby Peter) memoir, What Was Said to Me. She was a matriarch from the Cowichan First Nation on Vancouver Island, near the town of Duncan.

Unlike many Indigenous people across Canada, Sti'tum'atul'wut did not suffer the cruel life of being an 'inmate' at an Indian Residential School. She was able to do her schooling close to home and in the arms of loving parents where she began to learn and practice her Coast Salish culture at a young age.

Because of the early influence of her parents, who themselves were steeped in the traditions of their people, and being raised on a family-owned farm, Sti'tum'atul'wut was prepared for a tireless life of service to her people.

From the start, Sti'tum'atul'wut was generous with her cultural knowledge and helped those who returned home after spending years away at Indian Residential Schools. The Indian Residential Schools were developed to kill the Indian in the child as part of an assimilation experiment by the Canadian government under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Sti'tum'atul'wut assisted thousands of Cowichan residential school survivors regain a basic understanding of the language and culture they had lost at these cruel institutions.

Born on December 27, 1932, Sti'tum'atul'wut's life began simply enough. Up at daybreak to do work on the farm and then get ready for school. She said this gave her the work ethic to accomplish any difficult task.

She did not play games like softball as a child because her mother said "playing softball was just practising laziness." Practicing culture, on the other hand, is not for the faint of heart. It takes patience and a response to a higher calling.

Sti'tum'atul'wut learned much from her mother, Cecilia Leo. "The teachings always seemed to come when we were busy in the kitchen with my sisters," says Sti'tum'atul'wut. It was mostly me, because I was the oldest daughter. And she always talked to me and told me that what I see, to remember.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's mother also told her, What you learn from your parents is what you are going to have to pass down to the next generation.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's commitment to her Cowichan language, Hul'q'umi'num' led her later in life to participate in the development of a linguistics program to preserve the language. Over seven decades, she mentored students and teachers to develop a basic knowledge of Hul'q'umi'num'.

The importance of language cannot be understated. It is almost impossible to learn a culture without language. There are few similarities, if any, in cultural traditions surrounding spiritual practices around the world. Thus, Sti'tum'atul'wut offers insights into the unique spiritual practices of the Coast Salish in her memoir.

One such practice is commonly called a spirit bath ceremony in which the practitioner goes for a bath in the early morning hours before sunrise on a winter day. It is a time of prayer and spiritual cleansing. Spiritual practices are for the benefit of the people and they are known as medicine to Coast Salish people.

Like Sti'tum'atul'wut with her Cowichan language and culture, I prefer to speak in my language (Squamish) when I talk to other Squamish people about our spirituality. Everything seems clearer when spoken in our own language.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's contribution to her people make her a national treasure to them. Her legacy of resilience and advocacy for her people will live on through the generations she has taught.

In recognition of her tireless efforts in preserving Cowichan language and culture, Sti'tum'atul'wut was awarded two honourary doctoral degrees in 2019: one from Simon Fraser University and the other from the University of Victoria.

What Was Said to Me is a collaboration between Sti'tum'atul'wut and Helene Demers, a Canadian-Dutch cultural anthropologist and research associate at Vancouver Island University. Demers has done research in the Cowichan valley for the past 30 years.

Sti'tum'atul'wut was all about helping people to live their best life as Indigenous people.

She had the opportunity to visit many other Coast Salish communities throughout her lifetime. She experienced the different practices and was enriched by the diversity of customs. This taught her to respect and accept differences. It also gave her insight into how people strive to make the best of their lives.

She passed away on January 8, 2021 knowing that her memoir was set to be published. She has left a legacy on how we can all lead a life of harmony and purpose. As Sti'tum'atul'wut advises, "It will make me happy if you listen and hear and follow up your own traditions and our ways of life as Native people, and to know yourself and know your children, understand them, help them and give them all the support that you can give them.

Latash-Maurice Nahanee is a member of the Squamish Nation. He has a B.A. degree (Simon Fraser University).

BCBW 2021

ILMBC2

+++

BOOKS

Hukari, Thomas E. & Ruby Peter (editors). The Cowichan Dictionary of the Hul'qumin'um' Dialect of the Coast Salish People (Duncan: Cowichan Tribes, 1995).

What Was Said to Me: The Life of Sti'tum'atul'wut, a Cowichan Woman. In collaboration with Helene Demers. (Royal BC Museum, 2021) $24.95 9780772679383

[BCBW 2021]

+++

REVIEW 2021

by Latash-Maurice Nahanee

A life well-lived is captured in Sti'tum'atul'wut's (Ruby Peter) memoir, What Was Said to Me. She was a matriarch from the Cowichan First Nation on Vancouver Island, near the town of Duncan.

Unlike many Indigenous people across Canada, Sti'tum'atul'wut did not suffer the cruel life of being an 'inmate' at an Indian Residential School. She was able to do her schooling close to home and in the arms of loving parents where she began to learn and practice her Coast Salish culture at a young age.

Because of the early influence of her parents, who themselves were steeped in the traditions of their people, and being raised on a family-owned farm, Sti'tum'atul'wut was prepared for a tireless life of service to her people.

From the start, Sti'tum'atul'wut was generous with her cultural knowledge and helped those who returned home after spending years away at Indian Residential Schools. The Indian Residential Schools were developed to kill the Indian in the child as part of an assimilation experiment by the Canadian government under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Sti'tum'atul'wut assisted thousands of Cowichan residential school survivors regain a basic understanding of the language and culture they had lost at these cruel institutions.

Born on December 27, 1932, Sti'tum'atul'wut's life began simply enough. Up at daybreak to do work on the farm and then get ready for school. She said this gave her the work ethic to accomplish any difficult task.

She did not play games like softball as a child because her mother said "playing softball was just practising laziness." Practicing culture, on the other hand, is not for the faint of heart. It takes patience and a response to a higher calling.

Sti'tum'atul'wut learned much from her mother, Cecilia Leo. "The teachings always seemed to come when we were busy in the kitchen with my sisters," says Sti'tum'atul'wut. It was mostly me, because I was the oldest daughter. And she always talked to me and told me that what I see, to remember.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's mother also told her, What you learn from your parents is what you are going to have to pass down to the next generation.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's commitment to her Cowichan language, Hul'q'umi'num' led her later in life to participate in the development of a linguistics program to preserve the language. Over seven decades, she mentored students and teachers to develop a basic knowledge of Hul'q'umi'num'.

The importance of language cannot be understated. It is almost impossible to learn a culture without language. There are few similarities, if any, in cultural traditions surrounding spiritual practices around the world. Thus, Sti'tum'atul'wut offers insights into the unique spiritual practices of the Coast Salish in her memoir.

One such practice is commonly called a spirit bath ceremony in which the practitioner goes for a bath in the early morning hours before sunrise on a winter day. It is a time of prayer and spiritual cleansing. Spiritual practices are for the benefit of the people and they are known as medicine to Coast Salish people.

Like Sti'tum'atul'wut with her Cowichan language and culture, I prefer to speak in my language (Squamish) when I talk to other Squamish people about our spirituality. Everything seems clearer when spoken in our own language.

Sti'tum'atul'wut's contribution to her people make her a national treasure to them. Her legacy of resilience and advocacy for her people will live on through the generations she has taught.

In recognition of her tireless efforts in preserving Cowichan language and culture, Sti'tum'atul'wut was awarded two honourary doctoral degrees in 2019: one from Simon Fraser University and the other from the University of Victoria.

What Was Said to Me is a collaboration between Sti'tum'atul'wut and Helene Demers, a Canadian-Dutch cultural anthropologist and research associate at Vancouver Island University. Demers has done research in the Cowichan valley for the past 30 years.

Sti'tum'atul'wut was all about helping people to live their best life as Indigenous people.

She had the opportunity to visit many other Coast Salish communities throughout her lifetime. She experienced the different practices and was enriched by the diversity of customs. This taught her to respect and accept differences. It also gave her insight into how people strive to make the best of their lives.

She passed away on January 8, 2021 knowing that her memoir was set to be published. She has left a legacy on how we can all lead a life of harmony and purpose. As Sti'tum'atul'wut advises, "It will make me happy if you listen and hear and follow up your own traditions and our ways of life as Native people, and to know yourself and know your children, understand them, help them and give them all the support that you can give them.

Latash-Maurice Nahanee is a member of the Squamish Nation. He has a B.A. degree (Simon Fraser University).

BCBW 2021

ILMBC2

+++

Home

Home