LITERARY LOCATION: Temlaham Ranch, on Skeena River, near Chicago Creek, 55" 13.5' north and 127" 41.5' west

From 1975 to 2009, Neil Sterritt and his family lived at Temlaham Ranch, the site of a Gitxsan ancestral village on the Skeena River (a.k.a. Temlaxam or Dimlahamid), during which time he was hired as land claims director for the Gitksan-Carrier Tribal Council. A member of the House of Gitluudaahlxw, he was president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years leading up to the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case known as Delgamuukw v. BC.

As one of the principal architects of the 1987 -1990 court case, Sterritt was on the stand for 34 days during the Delgamuukw trial. He has since written extensively on aboriginal rights and governance and served as a consultant to many aboriginal organizations around the world, having co-authored Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed (UBC Press 1999).

*

In 2008 Sterritt received an honorary doctorate from the University of Toronto in recognition of his "lifetime contributions to the understanding and expression of aboriginal citizenship in Canada." He also served as Director of Self-government, Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa from 1988 to 1991.

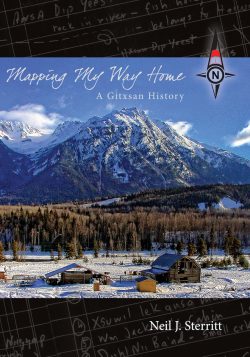

In Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016), Sterritt traces the history of the area at the junction of the Skeena and Bulkley Rivers, the resiliency of the First Nations residents who have maintained the villages of Gitanmaax and Hazelton, as well as his own personal story of growing up in Hazelton and helping his people fight the Delgamuukw court case. His overview stretches from the creation tales of Wiigyet to the advent of oil and gas pipeline proposals, including tales of the Madiigam Ts'uwii Aks (supernatural grizzly of the waters), the founding of Gitanmaax, Kispiox and Hagwilget and the coming of the fur traders, miners, packers, missionaries and telegraphers.

This book won the 2017 Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize for the best book to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia. In Mapping My Way Home, Gitxsan leader Neil Sterritt shares the stories of his people, both ancient and recent, to illustrate their resilience when faced with the challenges that newcomers brought. Stephen Hume calls this account from one of the Gitxsan architects of the Delgamuukw court decision a "remarkable, unique and articulate history...a powerful, accessible and cultural tour de force. It deserves to be on every British Columbian's bookshelf."

Neil Sterritt and his wife, Barbara, lived near Williams Lake. He died in 2020. See Obituary below.

--

HERE FOLLOWS NEIL STERRITT'S INTRODUCTION TO MAPPING MY WAY HOME

My parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles told exciting stories about growing up in northwest British Columbia. They laughed and joked, gossiped and teased. They spoke of amusing, larger than life people and romantic places along winding forest trails, places like Kisgegas, Kuldo, Bear Lake, Manson Creek, Telegraph Creek, the Omineca and Cassiar gold fields and the Yukon. Their stories gave texture and meaning to my mental maps. I longed to travel their trails, to experience those places for myself. Later in my life I did that, and went far beyond the familiar paths of my ancestors. Eventually I realized that maps, both imagined and real, can unite people and define their connection to the land, family, culture, language, history-to home.

But that would come later. I was born and raised in Hazelton in the 1940s. My father was born in a Gitxsan village, Glen Vowell, and my mother was born in a Newfoundland outport village, Little Bay Islands. Whenever we visited my Gitxsan grandparents, the adults spoke Gitxsan unless my mother was present and then, out of respect, they switched to English.

Hazelton was the white community, and Gitanmaax-the reserve just up the hill from our house-was the Gitxsan community. There were disputes and rivalries between the children of these communities but they were never serious. And when it came to sports and games, we all played together.

Horses and cows wandered the dirt streets and wood plank sidewalks. Because livestock ran free, everyone fenced their yards to protect their gardens. During spring breakup we all played in the melt water that ran down the hill and along Government Street, building dams and making hand-carved boats. We caught (and set free) swallows with simple bolo-like devices as they swooped about looking for nesting material. We played marbles and other children's games along the streets and in the school yard. The only building specifically designated a school was next to our house. It had one teacher who taught about twenty pupils in several lower grades. Empty buildings here and there about town provided makeshift classrooms for those in the higher grades. Barrel stoves were lit each cold morning to heat the schools. Our homes were heated the same way, with the addition of a McClary cook stove in the kitchen and a wood or coal heater in the front room. During winter we slid on sleighs, cardboard or tin or skied down Smith Hill and the hill by Gitanmaax hall, near our house.

Hazelton had three general stores, a drug store and confectionary, a hotel, three Chinese cafes and a Chinese laundry. Wong's laundry sat beside the Skeena across the road from our house. There we frequently watched Wong and his Chinese brethren smoke a bamboo water pipe.

There were three churches: Anglican, Catholic and Pentecostal. Although located off reserve, the Anglican Church hall also served as the Indian day school for those of our Gitxsan friends who did not attend residential school. Kids from mixed marriages went to the Hazelton Superior School in the lower grades. In the upper grades children of all races from the surrounding villages attended the Hazelton Amalgamated School. The school was opened in 1951 by the Gitanmaax Band Council, the Hazelton Municipal Council, BC provincial officials and local residents and was reputed to be the only school of its kind in Canada.

The Gitxsan children who did go to residential schools in places like Lejac, Lytton, Port Alberni and Edmonton in the fall usually came back in the spring. There is no doubt many Gitxsan children suffered different forms of abuse while attending residential school and some never came home again. Others benefited from the experience, picking up practical skills and acquiring an education. Some also formed lasting alliances at residential school that benefited both them and their communities as they battled for recognition of aboriginal rights and title to land in subsequent years.

Hazelton's community hall served many purposes: concerts and dances, meetings, recreation such as boxing and wrestling, badminton, basketball and volleyball, and afternoon and evening movies on Saturdays, with my father running the projector.

Government services included the Indian Agent, Forest Service ranger station, public works, the RCMP detachment and a jail. Telegraph services existed from about 1900, a telephone before 1921, and party lines from the late 1940s. A diesel generator, owned by R.S. Sargent & Company and operated by my father when he returned from Europe after WW II, provided electricity to most of the town. Several springs or wells provided fresh water to those fortunate to have them nearby. The rest of us packed water in buckets from the Skeena River year-round. Rainwater sufficed for laundry and bath water during spring, summer and fall. We, and most others, bathed in a galvanized tub in the kitchen for most of the 1940s.

Everyone had an outhouse, some with two-seaters for those who didn't mind the company on a freezing winter day. The United Church-sponsored hospital was built one mile from town in 1903 on land that Chief Gidumgaldo designated for that purpose.

Gitanmaax Reserve accommodated the Salvation Army church and the Salvation Army hall that doubled as a school. The Gitanmaax community hall was used for on reserve events such as dances, weddings, funerals and feasts, although feasts had to be held secretly because of federal legislation banning them. The ball field at Totem Park was on reserve, as was our swimming hole on the Bulkley Slough.

Employment along the Skeena was mainly seasonal, based on trapping, selective logging, farming and, for aboriginal people, the commercial fishery in the Skeena estuary near Prince Rupert. Government services, the hospital, several retail stores, the Silver Standard Mine and Marshall Brothers Trucking provided steady employment for some, including the blacksmith because horses were still the main mode of transportation. At the same time, everyone added to their meager incomes with large gardens and by harvesting domestic and wild berries, salmon and wild game. Potatoes and carrots were stored along with canned or jarred fruit and jams in frost-free cellars dug beneath kitchen floors. In summer, homemade root beer put up in beer bottles was kept cool there too, a treat not to be underestimated and almost equaled by Bud Dawson's ice cream which arrived weekly by train in large insulated canvas tubs.

Many Gitxsan families made a living logging spruce and hemlock trees for lumber and western redcedar trees for telephone poles. The BC Forest Service allocated timber limits to those wishing to log. Trees were felled with axes and crosscut saws. I recall my grandmother, Kate Sterritt, working at my grandfather Charlie's pole camp. She might fall and peel a twenty-five or thirty-foot cedar tree between lunch and supper. She was as much a driver of their business as my grandfather. She too was an entrepreneur and managed their rental cabins in Hazelton.

One afternoon she came walking down the hill towards us on her way home. She had a four-gallon cedar bent box filled with huckleberries on her back and was followed by two large dogs with packs. She had been away alone for several days picking berries about eight kilometres from town.

Although she had limited writing skills, she knew how to delegate. I recall on two occasions when she needed to convey a message and told me what to say as I printed the letters for her.

Sawmill owners hauled their lumber to R.S. Sargent's in Hazelton or to the railroad in New Hazelton. Some pole camps hired Marshall Brothers Trucking to haul their poles to the railroad. Others floated their winter's harvest down the Skeena in river drives. This was an annual event when we watched the men break up logjams and send the poles past the village of Hazelton. The poles were gathered in a boom that spanned the Skeena River at Nash Y, about a kilometre below the village of Gitsegucla. There men brought the poles ashore and, using a cable powered by a mechanical donkey, skidded them up a high, steep hill to the railroad on the right bank of the Skeena where men loaded them onto flat deck rail cars and shipped them to Minnesota.

We lived in a house at the east end of Government Street near St. Peter's Church. We often played along Government Street which, at that time, was the main road from Hazelton to the world as we knew it-Kispiox, New Hazelton, Prince Rupert, Prince George and Vancouver. My grandparents lived about two blocks southwest of us, also on Government Street. Once, my friends and I were making bows and arrows in my grandparents' yard. I struggled with my bow but managed finally to get the red willow carved, bent and strung. My grandfather, who was chopping wood nearby, summoned me as I began to carve an arrow. He chose a piece of cedar kindling and with his jackknife whittled it expertly until the business end was blunt, the other end notched. He said, "You can kill a rabbit, squirrel or grouse with this, but you can take someone's eye out with the arrow you are making."

A small Catholic Church that my grandmother supported was built on Hankin Street around the corner from my grandparent's house. She once asked my cousin Johnny and me to accompany her there. She had a child-sized fedora, which we called a gaytim (hat) Boston (American), for each of us to wear. We may have been six or seven years old and off we went, two little men wearing our fancy toppers.

Frank Harris and his wife lived above the Bulkley River at the southwest end of Gitanmaax. Frank had an apple tree and four of us snuck into his yard, picked apples and ran off. We ate them down at the slough. A day or so later my grandmother summoned us to her house. She sat us in a row, held court and let us off with a lecture.

In March of 1956, when I was fifteen, I quit school. As with many teenagers, it was obvious to me that I knew far more than my teachers and we weren't getting along. I went to work for my father who had a pole camp along the left bank of the Skeena River north of Hazelton. He put me to work packing boulders from the road he was building with his D4 bulldozer. It took a pretty smart guy to do that kind of work.

Dad started his pole business in 1948 using five-foot crosscut saws and work horses. By 1956 he had added a forty-pound power saw, the bulldozer and a team of horses to his outfit. I worked with him that summer, camping in a tent beside Sterritt Creek. I asked Dad how the creek got its name. He said he didn't know. I assumed he was being modest and that it was named for him or his father.

That fall my working days ended. I had been hunting mountain goat with several men who worked for my dad and arrived home on a Saturday evening in late September. When I walked into the house my mother said, "You are going back to school," and the next day I found myself on an airplane flying from Terrace to Vancouver. I might have gone back to school in Hazelton but was having a major dispute with one of the teachers there. Also, my mother knew I would be well cared for in Vancouver by relatives. Thus began my annual treks between Hazelton and Vancouver. My Aunt Margaret, Dad's sister, and her husband, Bill Heath, had just moved to the Lower mainland with their children and bought a house in East Vancouver. My mother arranged to have me board with them. I enrolled in Grade Nine at Gladstone, a high school nearby and spent the next four years there. I returned in the summers to work with my dad but didn't call Hazelton home again until my wife and I moved back in 1973.

But for Gladstone, I might not have met Barbara, the daughter of Bill and Irene Hepplewhite, who was born and raised in Vancouver. In 1960, a friend introduced us and we dated for a few months. In 1963 we again began dating and were married in Port Moody in September. Barbara's Aunt Hazel once read her tea leaves and said, "You are going to marry, have twins, and travel the world." Hazel was right about the marriage and travel, but our sons were born in New Westminster and Winnipeg three years apart.

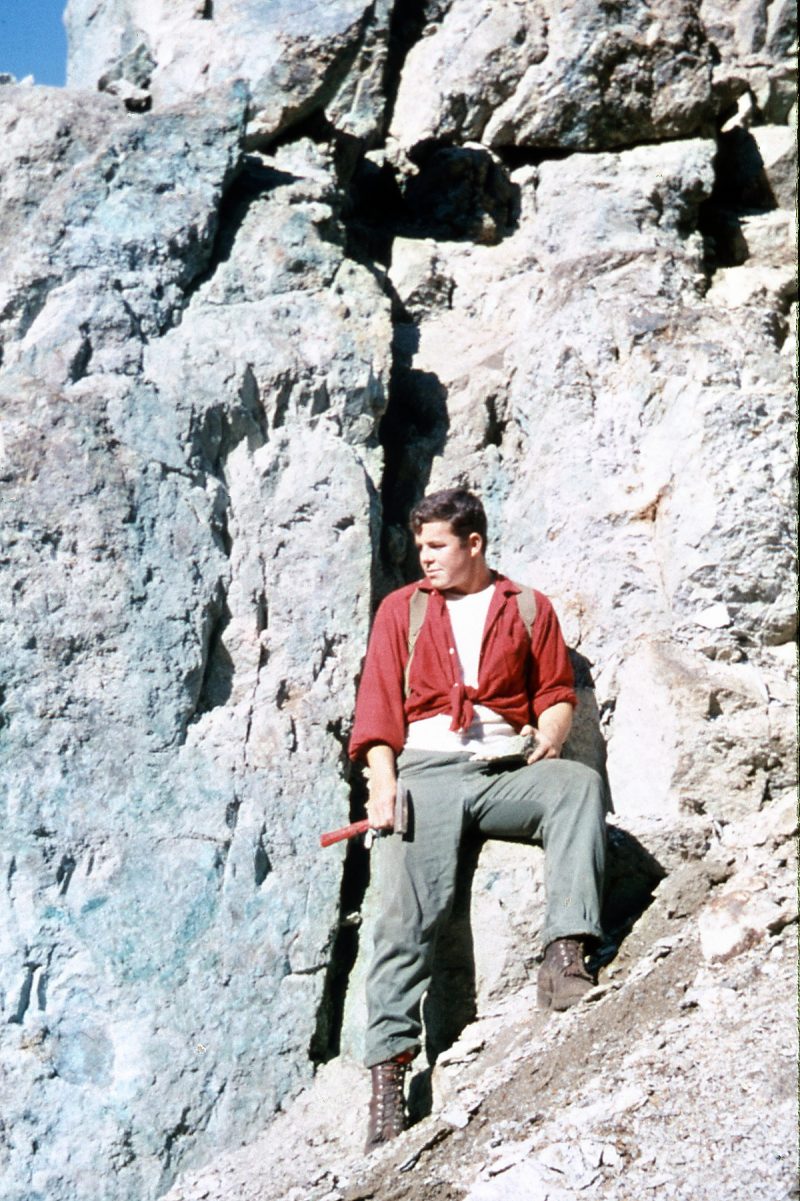

I graduated from Gladstone in 1960 and went to the University of British Columbia for the next two years, still working summers with my dad. In the spring of 1962 I landed a summer job as a field assistant with Kennco Explorations at their Galore Creek property in northwestern BC. Company geologists taught me about rocks and minerals and I also learned that topographic maps, air photos, compasses and notebooks are basic geologist's tools, used to plan field trips, and record key features and locations along the way. Later, in 1963, while still working with Kennco, I began to record information in the field that was transferred to working maps.

In the fall of 1964 I enrolled in the British Columbia Institute of Technology's two-year mining technology program which included courses in surveying, mapping and drafting. I worked for Amax Exploration at their Lucky Ship property near Morice Lake during the summers of 1965 and 1966. After I graduated, Amax hired me full time.

But back in 1962, after spending the summer prospecting in the Stikine Mountains near Telegraph Creek in northwestern BC, I visited my grandfather in Hazelton. He was seated at the kitchen table in the house he shared with his third wife, Jessie Lumm. When I told him I'd been to Telegraph Creek, he said he'd been there too, a long time ago:

"I was with some men driving cattle from the Chilcotin to the Yukon. It was a tough trip. The weather was bad. It rained most of that summer. Feed was scarce because other men were driving herds north too. Some of the horses died, and others were weak and lame and we abandoned them. We had to put packs on some of the cattle. I quit at Telegraph Creek and took a boat down the Stikine River to Wrangell, then to Port Essington and home to Hazelton."

My grandfather was in his mid-teens at the time.

The first lengthy journey I recall making was with my Uncle Walter, Dad's brother, in 1952. He was driving to Chilliwack to get an engine for the sawmill he was building near Hazelton. The drive took more than four days over gravel and dirt roads in my grandfather's one-ton Chevrolet truck. By contrast, the trips my grandparents took by foot, saddle horse, canoe and sternwheeler took weeks and sometimes months. And through my own journeys I have come to appreciate that the distances my grandparents traveled during their lifetimes-both geographically and culturally-began in the mists of time when our aboriginal ancestors first settled the Skeena Valley.

While the village of Gitanmaax is so ancient that its years may be numbered in the thousands, Hazelton has yet to mark its second century. Hazelton is an incorporated municipality a few kilometres off Highway 16 between the 20th century communities of Smithers and Terrace. It was founded in 1871 when the Omineca goldfields proved viable. Soon after, Gitanmaax and Hazelton became the hub of a transportation network along pre-existing aboriginal trails that radiated east to Babine Lake and the Omineca; south to Fort Fraser and the Cariboo; west down the Skeena to Port Essington and Fort Simpson; and north to the Yukon. Another trail running west from the villages of Gitwangak and Gitanyow also linked upper Skeena villages to Nisga'a villages on the lower Nass River.

Although Gitanmaax and Hazelton seem to share the same land base and services, there are significant historic and cultural differences between them. The colonial government surveyed the townsite of Hazelton and granted it thirteen acres of land in 1871. Canada imposed a 2,400-acre Indian Reserve on Gitanmaax villagers in the 1890s, although territories belonging to Gitanmaax chiefs run to the height of land of the surrounding mountains and east more than fifty kilometres to the Suskwa River headwaters. Today Gitanmaax falls under the jurisdiction of the federal Indian Act while Hazelton falls under the jurisdiction of the provincial Municipal Act.

A casual visitor could be forgiven for assuming Hazelton is larger than thirteen acres. Gitanmaax and Hazelton appear to be one community with the reserve boundary bordering the town's. On the side of the road by our house stood St. Peter's Anglican Church. Nearby, overlooking Hazelton and the church, stood Gidumgaldo's totem pole. The pole and the church symbolize very different histories, customs, values and beliefs. Gidumgaldo's totem pole was carved and erected in 1881; St. Peter's Church was built twenty years later. Gidumgaldo's long house once stood behind the pole. My grandfather, Charlie Sterritt, was born there, in Gidumgaldo's house, in 1885.

BOOKS:

Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed (UBC Press 1999). Co-author.

Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016) 978-1-928195-01-6 (Hardcover); 978-1-928195-02-3 (Paper); Price: $39.95 (Hardcover); $29.95 (Paper)

[BCBW 2017]

ORDER OF BC

Neil Sterritt made major contributions to British Columbia and to First Nations over many years, working tirelessly and selflessly both to strengthen his people's proven ability to embrace opportunities while holding onto traditional values. He brought all British Columbians together on the common ground of hope and possibility.

Born in Gitxsan territory, Mr. Sterritt left the northwest as a young man to study and work in the minerals exploration industry throughout Canada, overseas and in the USA. He returned in the early 1970s as manager of the 'Ksan Historic Village and Museum, and served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council. While president, he was involved on behalf of his people in the National Aboriginal Constitutional Conferences during the 1980s and the Charlottetown Constitutional Conference in the early 1990s.

Mr. Sterritt served as Director of Land Claims and Self-government with the Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa. He worked with more than 100 elders in identifying and mapping the traditional Gitxsan territories, an effort that was the basis of the court action that became known as the Delgamuukw case.

For many years, Mr. Sterritt led governance workshops aimed at assisting Aboriginal communities make the difficult transition from paternalism to self-reliance. In this work with most of the B.C. and Yukon First Nations, he explained legal and fiduciary responsibilities in the context of First Nations' culture and traditions.

A leader in land claims and other First Nations issues over many years, Mr. Sterritt was well known outside of Canada, having been invited to lecture, advise and tour aboriginal communities in Australia, East Malaysia, New Zealand, Norway, Thailand and the United States.

Mr. Sterritt was awarded the BC Book Prizes Roderick Haig-Brown Award for his book Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History and an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Victoria.

OBITUARY:

It is with great sadness we announce the passing of Neil John Sterritt on April 9th, 2020, in Williams Lake, BC.

Neil is survived by Barbara, his loving wife of 56 years, sons: Gordon (Cici) and Jamie, grandchildren: Todd (Brittany), Cory (Makayla), Kreg, Elena, Cassidie and great-grandson Knox.

Also survived by sister Shirley Muldon (Earl), brothers Jamey, Arthur (Patricia), Richard (Marlese), Roger (Josie), stepmother Barbara Jean, sister-in-law Teri Hepplewhite and many nieces, nephews and other relatives and friends around the world.

He was predeceased by his father Neil Benjamin and his mother, Alma Jean.

Born and raised in Hazelton, BC, Neil's love for the land and its people was evident through all stages and aspects of his life. His hereditary name was Madiigam Gyamk, from the Gitxsan House of Gitluudaahlxw.

Neil met his wife to be (Barbara Hepplewhite) at Gladstone Secondary, graduating in 1960. He attended UBC and eventually enrolled in the Mining Diploma program at BCIT, where he emerged from the first BCIT graduating class in 1966.

Life took him many places, living and working throughout BC, Yukon, Manitoba, Ireland, Arizona, Ottawa and eventually 150 Mile House. While these were all special to him, his home was always Hazelton and their beloved Temlaham Ranch on the banks of the Skeena River.

His early career included logging with his father and working in mining exploration during the summers while still attending school. He worked for Kennecott Exploration, Amax Exploration, 'Ksan Historical Village, the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council, Assembly of First Nations and with countless First Nations communities and organizations throughout BC and the Yukon.

Always working with and on behalf of his nation, he helped advance Aboriginal Rights and Title at the local, Provincial and National levels. Much of his work set the stage that launched the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case, Delgamuukw v. The Queen, where in 1987/88, he spent 34 days on the stand as an expert witness defending the knowledge of Gitxsan Elders and leaders.

He was also co-chair of the Federal-Provincial Constitutional round on Aboriginal Issues for the Charlottetown Accord and a mediator during the Oka Crisis.

In 1992 Neil established Sterritt Consulting, where until just recently, he utilized his vast experience to assist indigenous organizations with aboriginal and treaty rights, self-government and leadership skills development.

Neil participated on many governing bodies, including the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology, Royal BC Museum and Royal Canadian Geographical Society, as well as many commissions and committees worldwide. This included extensive work and speaking engagements in Australia, New Zealand, Norway, East Malaysia, Thailand and the United States.

He authored many articles, papers and books of which his pride was "Mapping My Way Home, A Gitxsan History." A culmination of years spent researching his Gitxsan and European roots. The book received the 2017 BC Book Prize Roderick Haig-Brown Award and second place in the 2017 BC Historical Federation for Historical Writing.

Considered by many to be an extraordinary man for his passion, humility and integrity, everything he did, he poured his heart into. He was extremely honoured and proud to be awarded the Queen Elizabeth Golden Jubilee Medal (2002), Honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from the University of Toronto (2008) and University of Victoria (2017) and the Order of British Columbia (2017).

While this is a short glimpse into his incredible life and accomplishments, of which his most significant was his family -- in Neil's words if you would like to know more, "...it's in the book."

In lieu of flowers or donations, we ask that you spend time with your loved ones, enjoy the outdoors or raise a glass of your finest and toast to lasting, lifelong friendships and beyond. This is what he would wish for you.

At a time when we can safely gather, a Celebration of Neil's life will be held in Hazelton BC.

Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History

by Neil J. Sterritt

Smithers: Creekstone Press, 2016.

$29.95 / 9781928195023

Reviewed by Dorothy Kennedy

*

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council in the 1980s.

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council in the 1980s.

From 1975 to 2009, Neil Sterritt and his family lived at Temlaham Ranch, the site of a Gitxsan ancestral village on the Skeena River (a.k.a. Temlaxam or Dimlahamid), during which time he was hired as land claims director for the Gitksan-Carrier Tribal Council. A member of the House of Gitluudaahlxw, he was president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years leading up to the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case known as Delgamuukw v. B.C.

Between 1984 and 1991 the case known as Delgamuukw v. British Columbia made its way through the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en people claimed title to over 58,000 square km of B.C.

Two Gitxsan chiefs held the hereditary name Delgamuukw during the court case: Albert Tait, who was Delgamuukw during the preparation of the trial, and Kispiox carver Earl Muldoe, who assumed the name in 1987 after Tait's death. On the Wet'suwet'en side the chief was Alfred Joseph, whose chiefly name was Dini ze' Gisday'wa.

In his judgment of March 1991, Chief Justice Allan McEachern dismissed the role of oral history and determined that Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en title was extinguished when B.C. joined Confederation. In his infamous judgement, McEachern opined that:

[caption id="attachment_34102" align="alignleft" width="250"] Judge Allan McEachern, 1993. "Nasty, brutish and short."[/caption]

Judge Allan McEachern, 1993. "Nasty, brutish and short."[/caption]

It would not be accurate to assume that even pre-contact existence in the territory was in the least bit idyllic. The plaintiffs' ancestors had no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles, slavery and starvation was not uncommon, wars with neighbouring peoples were common, and there is no doubt, to quote Hobbes, that aboriginal life in the territory was, at best, "nasty, brutish and short."

The Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en appealed appealed McEachern's ruling to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in 1997 that the B.C. government had no right to extinguish the Indigenous peoples' claim to their ancestral territories and that oral history was a legitimate type of evidence.

Reviewer Dorothy Kennedy concludes that, in Mapping My Way Home, Neil Sterritt "has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people's place and history in this province and this book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw."

In Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016), Sterritt traces the history of the area at the junction of the Skeena and Bulkley Rivers, the resiliency of the First Nations residents who have maintained the villages of Gitanmaax and Hazelton, as well as his own personal story of growing up in Hazelton and helping his people fight the Delgamuukw court case. His overview stretches from the creation tales of Wiigyet to the advent of oil and gas pipeline proposals, including tales of the Madiigam Ts'uwii Aks (supernatural grizzly of the waters), the founding of Gitanmaax, Kispiox and Hagwilget and the coming of the fur traders, miners, packers, missionaries and telegraphers.

Mapping My Way Home was awarded the 2017 Roderick Haig-Brown Region Prize for the best book to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia, an honour thoughtfully bestowed upon an author who has contributed greatly to the history of our province through contextualizing and elucidating his people's oral history that almost thirty years ago evaded Chief Justice McEachern's appreciation. - Ed.

*

The Delgamuukw v. British Columbia litigation in the Supreme Court of British Columbia provoked many responses and much scientific and legal discussion about the nature and reliability of oral history.

Among the most prominent anthropological and historical specialists reflecting on these questions was a collection of scientists whose criticism of the Court appeared in a special issue (Autumn 1992, vol. 95) of BC Studies, entitled Anthropology and History in the Courts. Guest Editor Bruce Miller concluded from these articles that the materials submitted to the Court by anthropologists and historians "were improperly utilized and badly understood."

Certainly, Chief Justice Allan McEachern's lengthy "Reasons for Judgement" of 1991 on this long and costly trial presented a large target for anthropologists whose rebuttal to his stinging dismissal of their discipline resulted in a mass outcry, along with some more solemn and private self-reflection. Subsequent court witnesses have both profited and suffered from the backlash, learning from the earlier Court's reaction that experts, when amassing and analyzing oral histories, need to apply the tools of their profession more transparently.

The Court told us that evidence used within the restrictions of the western legal and political system, where the people-land relationships have been misrecognized by law and by policy, also requires greater attention to the historical context of the information and the recognition of conflicting stories.

If, paradoxically, Delgamuukw served anthropology well in bringing about more critical self-reflection of its methods, it served the First Nations even better by necessitating the collection of oral histories dispersed among elders and archives into a coherent story that connected a people to its homeland.

For Neil Sterritt, a member of the Gitxsan and author of Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History, research undertaken in preparation for the litigation immersed him in an ancient world created at Temlaham, a place he knew as a child, left as a teenager to pursue schooling and an international career in geology, and returned to as an adult where he served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years in those communities' preparation for Delgamuukw.

Strategy developed for the trial preparation in a series of meetings with Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en elders between 1981 and 1984 led to the transfer of the chiefs' knowledge of their territories onto maps and the collation of supporting documentation. The materials discussed boundaries of Houses, confirmed specific place names, and recorded descriptions of landmarks and resource use that together would present the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en chiefs' views of their world.

Sterritt and a team of researchers spent eight years building upon earlier ethnographic studies, including Sterritt's own mapping project begun in 1975. As Sterritt explains, "Contrary to the strategy used in the Calder case [1973] where one expert witness [anthropologist Wilson Duff] was called to prove title, our strategy was to defeat the extinguishment argument and to prove Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en title by placing a substantial body of evidence from the elders about our land, laws and oral histories against the meagre evidence of the crown and its sovereignty assertions" (p. 310).

Delgamuukw is significant, for the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 unanimously decided that Aboriginal title consists of the right to exclusively use and occupy the land including the right to choose how the land can be used.

However, what the Gitxsan gained from the litigation was more than an impressive legal victory, for they created an archives and library that should continue to provide an enduring legacy of their people's history from the mythical time of Temlaham through to their people's role in Canada's recognition of landmark legal principles.

For Neil Sterritt, what emerged from his preparation for the litigation was a deeper comprehension of his homeland. In Mapping My Way Home, it is through Sterritt's integration of the many forms of evidence compiled for the trial that the people-land relationships of the Gitxsan become clearly apparent.

His skilful weaving together of his personal journey of discovery with the accounts of ancestors and elders, coupled with historical and resource-use maps, and with the histories of both the local settler and Indigenous communities along with that of his Newfoundland mother, provides a more familiar and accessible route towards understanding the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en and their territories than any of the documents alone.

With such a volume of materials to draw from, including numerous expert reports, Sterritt's book is at times dense; at 354 pages it is far-reaching. But Sterritt has selected and told his story well. He has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people's place and history in this province. This book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw.

Dorothy Kennedy is a consulting anthropologist, occasional university lecturer and expert witness specializing in the Indigenous cultures of British Columbia, Washington State and, most recently, Alberta and the Yukon. She completed a Doctorate from the University of Oxford in 2000, and an award-winning Master's degree from the University of Victoria, where she has taught in the Anthropology Department and the Indigenous Education Program. For the past four decades, including two decades devoted intensively to ethnographic and linguistic fieldwork in First Nations' communities, she has been engaged full-time in the research process, from conceptual planning and document review to issue-focused research, analysis, and reporting. She is the author or co-author (primarily with her colleague and husband, Randy Bouchard), of hundreds of reports, as well as numerous published articles and books, both scientific and popular, including four articles in the Plateau and Northwest Coast volumes of the Smithsonian Institution's Handbook of North American Indians and, most-recently, Talonbooks' The Lil'wat World of Charlie Mack (2010). Kennedy and Bouchard are also editors of the well-acclaimed Indian Myths and Legends from the North-Pacific Coast of America, a translation of Franz Boas's first and significant collection of B.C. First Nations' mythology published by Talonbooks in 2002, and originally published in German in 1895. As of 2018, she was with Bouchard & Kennedy Research Consultants at Mill Bay, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Reviewis a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

"Only connect." - E.M. Forster

From 1975 to 2009, Neil Sterritt and his family lived at Temlaham Ranch, the site of a Gitxsan ancestral village on the Skeena River (a.k.a. Temlaxam or Dimlahamid), during which time he was hired as land claims director for the Gitksan-Carrier Tribal Council. A member of the House of Gitluudaahlxw, he was president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years leading up to the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case known as Delgamuukw v. BC.

As one of the principal architects of the 1987 -1990 court case, Sterritt was on the stand for 34 days during the Delgamuukw trial. He has since written extensively on aboriginal rights and governance and served as a consultant to many aboriginal organizations around the world, having co-authored Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed (UBC Press 1999).

*

In 2008 Sterritt received an honorary doctorate from the University of Toronto in recognition of his "lifetime contributions to the understanding and expression of aboriginal citizenship in Canada." He also served as Director of Self-government, Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa from 1988 to 1991.

In Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016), Sterritt traces the history of the area at the junction of the Skeena and Bulkley Rivers, the resiliency of the First Nations residents who have maintained the villages of Gitanmaax and Hazelton, as well as his own personal story of growing up in Hazelton and helping his people fight the Delgamuukw court case. His overview stretches from the creation tales of Wiigyet to the advent of oil and gas pipeline proposals, including tales of the Madiigam Ts'uwii Aks (supernatural grizzly of the waters), the founding of Gitanmaax, Kispiox and Hagwilget and the coming of the fur traders, miners, packers, missionaries and telegraphers.

This book won the 2017 Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize for the best book to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia. In Mapping My Way Home, Gitxsan leader Neil Sterritt shares the stories of his people, both ancient and recent, to illustrate their resilience when faced with the challenges that newcomers brought. Stephen Hume calls this account from one of the Gitxsan architects of the Delgamuukw court decision a "remarkable, unique and articulate history...a powerful, accessible and cultural tour de force. It deserves to be on every British Columbian's bookshelf."

Neil Sterritt and his wife, Barbara, lived near Williams Lake. He died in 2020. See Obituary below.

--

HERE FOLLOWS NEIL STERRITT'S INTRODUCTION TO MAPPING MY WAY HOME

My parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles told exciting stories about growing up in northwest British Columbia. They laughed and joked, gossiped and teased. They spoke of amusing, larger than life people and romantic places along winding forest trails, places like Kisgegas, Kuldo, Bear Lake, Manson Creek, Telegraph Creek, the Omineca and Cassiar gold fields and the Yukon. Their stories gave texture and meaning to my mental maps. I longed to travel their trails, to experience those places for myself. Later in my life I did that, and went far beyond the familiar paths of my ancestors. Eventually I realized that maps, both imagined and real, can unite people and define their connection to the land, family, culture, language, history-to home.

But that would come later. I was born and raised in Hazelton in the 1940s. My father was born in a Gitxsan village, Glen Vowell, and my mother was born in a Newfoundland outport village, Little Bay Islands. Whenever we visited my Gitxsan grandparents, the adults spoke Gitxsan unless my mother was present and then, out of respect, they switched to English.

Hazelton was the white community, and Gitanmaax-the reserve just up the hill from our house-was the Gitxsan community. There were disputes and rivalries between the children of these communities but they were never serious. And when it came to sports and games, we all played together.

Horses and cows wandered the dirt streets and wood plank sidewalks. Because livestock ran free, everyone fenced their yards to protect their gardens. During spring breakup we all played in the melt water that ran down the hill and along Government Street, building dams and making hand-carved boats. We caught (and set free) swallows with simple bolo-like devices as they swooped about looking for nesting material. We played marbles and other children's games along the streets and in the school yard. The only building specifically designated a school was next to our house. It had one teacher who taught about twenty pupils in several lower grades. Empty buildings here and there about town provided makeshift classrooms for those in the higher grades. Barrel stoves were lit each cold morning to heat the schools. Our homes were heated the same way, with the addition of a McClary cook stove in the kitchen and a wood or coal heater in the front room. During winter we slid on sleighs, cardboard or tin or skied down Smith Hill and the hill by Gitanmaax hall, near our house.

Hazelton had three general stores, a drug store and confectionary, a hotel, three Chinese cafes and a Chinese laundry. Wong's laundry sat beside the Skeena across the road from our house. There we frequently watched Wong and his Chinese brethren smoke a bamboo water pipe.

There were three churches: Anglican, Catholic and Pentecostal. Although located off reserve, the Anglican Church hall also served as the Indian day school for those of our Gitxsan friends who did not attend residential school. Kids from mixed marriages went to the Hazelton Superior School in the lower grades. In the upper grades children of all races from the surrounding villages attended the Hazelton Amalgamated School. The school was opened in 1951 by the Gitanmaax Band Council, the Hazelton Municipal Council, BC provincial officials and local residents and was reputed to be the only school of its kind in Canada.

The Gitxsan children who did go to residential schools in places like Lejac, Lytton, Port Alberni and Edmonton in the fall usually came back in the spring. There is no doubt many Gitxsan children suffered different forms of abuse while attending residential school and some never came home again. Others benefited from the experience, picking up practical skills and acquiring an education. Some also formed lasting alliances at residential school that benefited both them and their communities as they battled for recognition of aboriginal rights and title to land in subsequent years.

Hazelton's community hall served many purposes: concerts and dances, meetings, recreation such as boxing and wrestling, badminton, basketball and volleyball, and afternoon and evening movies on Saturdays, with my father running the projector.

Government services included the Indian Agent, Forest Service ranger station, public works, the RCMP detachment and a jail. Telegraph services existed from about 1900, a telephone before 1921, and party lines from the late 1940s. A diesel generator, owned by R.S. Sargent & Company and operated by my father when he returned from Europe after WW II, provided electricity to most of the town. Several springs or wells provided fresh water to those fortunate to have them nearby. The rest of us packed water in buckets from the Skeena River year-round. Rainwater sufficed for laundry and bath water during spring, summer and fall. We, and most others, bathed in a galvanized tub in the kitchen for most of the 1940s.

Everyone had an outhouse, some with two-seaters for those who didn't mind the company on a freezing winter day. The United Church-sponsored hospital was built one mile from town in 1903 on land that Chief Gidumgaldo designated for that purpose.

Gitanmaax Reserve accommodated the Salvation Army church and the Salvation Army hall that doubled as a school. The Gitanmaax community hall was used for on reserve events such as dances, weddings, funerals and feasts, although feasts had to be held secretly because of federal legislation banning them. The ball field at Totem Park was on reserve, as was our swimming hole on the Bulkley Slough.

Employment along the Skeena was mainly seasonal, based on trapping, selective logging, farming and, for aboriginal people, the commercial fishery in the Skeena estuary near Prince Rupert. Government services, the hospital, several retail stores, the Silver Standard Mine and Marshall Brothers Trucking provided steady employment for some, including the blacksmith because horses were still the main mode of transportation. At the same time, everyone added to their meager incomes with large gardens and by harvesting domestic and wild berries, salmon and wild game. Potatoes and carrots were stored along with canned or jarred fruit and jams in frost-free cellars dug beneath kitchen floors. In summer, homemade root beer put up in beer bottles was kept cool there too, a treat not to be underestimated and almost equaled by Bud Dawson's ice cream which arrived weekly by train in large insulated canvas tubs.

Many Gitxsan families made a living logging spruce and hemlock trees for lumber and western redcedar trees for telephone poles. The BC Forest Service allocated timber limits to those wishing to log. Trees were felled with axes and crosscut saws. I recall my grandmother, Kate Sterritt, working at my grandfather Charlie's pole camp. She might fall and peel a twenty-five or thirty-foot cedar tree between lunch and supper. She was as much a driver of their business as my grandfather. She too was an entrepreneur and managed their rental cabins in Hazelton.

One afternoon she came walking down the hill towards us on her way home. She had a four-gallon cedar bent box filled with huckleberries on her back and was followed by two large dogs with packs. She had been away alone for several days picking berries about eight kilometres from town.

Although she had limited writing skills, she knew how to delegate. I recall on two occasions when she needed to convey a message and told me what to say as I printed the letters for her.

Sawmill owners hauled their lumber to R.S. Sargent's in Hazelton or to the railroad in New Hazelton. Some pole camps hired Marshall Brothers Trucking to haul their poles to the railroad. Others floated their winter's harvest down the Skeena in river drives. This was an annual event when we watched the men break up logjams and send the poles past the village of Hazelton. The poles were gathered in a boom that spanned the Skeena River at Nash Y, about a kilometre below the village of Gitsegucla. There men brought the poles ashore and, using a cable powered by a mechanical donkey, skidded them up a high, steep hill to the railroad on the right bank of the Skeena where men loaded them onto flat deck rail cars and shipped them to Minnesota.

We lived in a house at the east end of Government Street near St. Peter's Church. We often played along Government Street which, at that time, was the main road from Hazelton to the world as we knew it-Kispiox, New Hazelton, Prince Rupert, Prince George and Vancouver. My grandparents lived about two blocks southwest of us, also on Government Street. Once, my friends and I were making bows and arrows in my grandparents' yard. I struggled with my bow but managed finally to get the red willow carved, bent and strung. My grandfather, who was chopping wood nearby, summoned me as I began to carve an arrow. He chose a piece of cedar kindling and with his jackknife whittled it expertly until the business end was blunt, the other end notched. He said, "You can kill a rabbit, squirrel or grouse with this, but you can take someone's eye out with the arrow you are making."

A small Catholic Church that my grandmother supported was built on Hankin Street around the corner from my grandparent's house. She once asked my cousin Johnny and me to accompany her there. She had a child-sized fedora, which we called a gaytim (hat) Boston (American), for each of us to wear. We may have been six or seven years old and off we went, two little men wearing our fancy toppers.

Frank Harris and his wife lived above the Bulkley River at the southwest end of Gitanmaax. Frank had an apple tree and four of us snuck into his yard, picked apples and ran off. We ate them down at the slough. A day or so later my grandmother summoned us to her house. She sat us in a row, held court and let us off with a lecture.

In March of 1956, when I was fifteen, I quit school. As with many teenagers, it was obvious to me that I knew far more than my teachers and we weren't getting along. I went to work for my father who had a pole camp along the left bank of the Skeena River north of Hazelton. He put me to work packing boulders from the road he was building with his D4 bulldozer. It took a pretty smart guy to do that kind of work.

Dad started his pole business in 1948 using five-foot crosscut saws and work horses. By 1956 he had added a forty-pound power saw, the bulldozer and a team of horses to his outfit. I worked with him that summer, camping in a tent beside Sterritt Creek. I asked Dad how the creek got its name. He said he didn't know. I assumed he was being modest and that it was named for him or his father.

That fall my working days ended. I had been hunting mountain goat with several men who worked for my dad and arrived home on a Saturday evening in late September. When I walked into the house my mother said, "You are going back to school," and the next day I found myself on an airplane flying from Terrace to Vancouver. I might have gone back to school in Hazelton but was having a major dispute with one of the teachers there. Also, my mother knew I would be well cared for in Vancouver by relatives. Thus began my annual treks between Hazelton and Vancouver. My Aunt Margaret, Dad's sister, and her husband, Bill Heath, had just moved to the Lower mainland with their children and bought a house in East Vancouver. My mother arranged to have me board with them. I enrolled in Grade Nine at Gladstone, a high school nearby and spent the next four years there. I returned in the summers to work with my dad but didn't call Hazelton home again until my wife and I moved back in 1973.

But for Gladstone, I might not have met Barbara, the daughter of Bill and Irene Hepplewhite, who was born and raised in Vancouver. In 1960, a friend introduced us and we dated for a few months. In 1963 we again began dating and were married in Port Moody in September. Barbara's Aunt Hazel once read her tea leaves and said, "You are going to marry, have twins, and travel the world." Hazel was right about the marriage and travel, but our sons were born in New Westminster and Winnipeg three years apart.

I graduated from Gladstone in 1960 and went to the University of British Columbia for the next two years, still working summers with my dad. In the spring of 1962 I landed a summer job as a field assistant with Kennco Explorations at their Galore Creek property in northwestern BC. Company geologists taught me about rocks and minerals and I also learned that topographic maps, air photos, compasses and notebooks are basic geologist's tools, used to plan field trips, and record key features and locations along the way. Later, in 1963, while still working with Kennco, I began to record information in the field that was transferred to working maps.

In the fall of 1964 I enrolled in the British Columbia Institute of Technology's two-year mining technology program which included courses in surveying, mapping and drafting. I worked for Amax Exploration at their Lucky Ship property near Morice Lake during the summers of 1965 and 1966. After I graduated, Amax hired me full time.

But back in 1962, after spending the summer prospecting in the Stikine Mountains near Telegraph Creek in northwestern BC, I visited my grandfather in Hazelton. He was seated at the kitchen table in the house he shared with his third wife, Jessie Lumm. When I told him I'd been to Telegraph Creek, he said he'd been there too, a long time ago:

"I was with some men driving cattle from the Chilcotin to the Yukon. It was a tough trip. The weather was bad. It rained most of that summer. Feed was scarce because other men were driving herds north too. Some of the horses died, and others were weak and lame and we abandoned them. We had to put packs on some of the cattle. I quit at Telegraph Creek and took a boat down the Stikine River to Wrangell, then to Port Essington and home to Hazelton."

My grandfather was in his mid-teens at the time.

The first lengthy journey I recall making was with my Uncle Walter, Dad's brother, in 1952. He was driving to Chilliwack to get an engine for the sawmill he was building near Hazelton. The drive took more than four days over gravel and dirt roads in my grandfather's one-ton Chevrolet truck. By contrast, the trips my grandparents took by foot, saddle horse, canoe and sternwheeler took weeks and sometimes months. And through my own journeys I have come to appreciate that the distances my grandparents traveled during their lifetimes-both geographically and culturally-began in the mists of time when our aboriginal ancestors first settled the Skeena Valley.

While the village of Gitanmaax is so ancient that its years may be numbered in the thousands, Hazelton has yet to mark its second century. Hazelton is an incorporated municipality a few kilometres off Highway 16 between the 20th century communities of Smithers and Terrace. It was founded in 1871 when the Omineca goldfields proved viable. Soon after, Gitanmaax and Hazelton became the hub of a transportation network along pre-existing aboriginal trails that radiated east to Babine Lake and the Omineca; south to Fort Fraser and the Cariboo; west down the Skeena to Port Essington and Fort Simpson; and north to the Yukon. Another trail running west from the villages of Gitwangak and Gitanyow also linked upper Skeena villages to Nisga'a villages on the lower Nass River.

Although Gitanmaax and Hazelton seem to share the same land base and services, there are significant historic and cultural differences between them. The colonial government surveyed the townsite of Hazelton and granted it thirteen acres of land in 1871. Canada imposed a 2,400-acre Indian Reserve on Gitanmaax villagers in the 1890s, although territories belonging to Gitanmaax chiefs run to the height of land of the surrounding mountains and east more than fifty kilometres to the Suskwa River headwaters. Today Gitanmaax falls under the jurisdiction of the federal Indian Act while Hazelton falls under the jurisdiction of the provincial Municipal Act.

A casual visitor could be forgiven for assuming Hazelton is larger than thirteen acres. Gitanmaax and Hazelton appear to be one community with the reserve boundary bordering the town's. On the side of the road by our house stood St. Peter's Anglican Church. Nearby, overlooking Hazelton and the church, stood Gidumgaldo's totem pole. The pole and the church symbolize very different histories, customs, values and beliefs. Gidumgaldo's totem pole was carved and erected in 1881; St. Peter's Church was built twenty years later. Gidumgaldo's long house once stood behind the pole. My grandfather, Charlie Sterritt, was born there, in Gidumgaldo's house, in 1885.

BOOKS:

Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed (UBC Press 1999). Co-author.

Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016) 978-1-928195-01-6 (Hardcover); 978-1-928195-02-3 (Paper); Price: $39.95 (Hardcover); $29.95 (Paper)

[BCBW 2017]

ORDER OF BC

Neil Sterritt made major contributions to British Columbia and to First Nations over many years, working tirelessly and selflessly both to strengthen his people's proven ability to embrace opportunities while holding onto traditional values. He brought all British Columbians together on the common ground of hope and possibility.

Born in Gitxsan territory, Mr. Sterritt left the northwest as a young man to study and work in the minerals exploration industry throughout Canada, overseas and in the USA. He returned in the early 1970s as manager of the 'Ksan Historic Village and Museum, and served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council. While president, he was involved on behalf of his people in the National Aboriginal Constitutional Conferences during the 1980s and the Charlottetown Constitutional Conference in the early 1990s.

Mr. Sterritt served as Director of Land Claims and Self-government with the Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa. He worked with more than 100 elders in identifying and mapping the traditional Gitxsan territories, an effort that was the basis of the court action that became known as the Delgamuukw case.

For many years, Mr. Sterritt led governance workshops aimed at assisting Aboriginal communities make the difficult transition from paternalism to self-reliance. In this work with most of the B.C. and Yukon First Nations, he explained legal and fiduciary responsibilities in the context of First Nations' culture and traditions.

A leader in land claims and other First Nations issues over many years, Mr. Sterritt was well known outside of Canada, having been invited to lecture, advise and tour aboriginal communities in Australia, East Malaysia, New Zealand, Norway, Thailand and the United States.

Mr. Sterritt was awarded the BC Book Prizes Roderick Haig-Brown Award for his book Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History and an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Victoria.

OBITUARY:

It is with great sadness we announce the passing of Neil John Sterritt on April 9th, 2020, in Williams Lake, BC.

Neil is survived by Barbara, his loving wife of 56 years, sons: Gordon (Cici) and Jamie, grandchildren: Todd (Brittany), Cory (Makayla), Kreg, Elena, Cassidie and great-grandson Knox.

Also survived by sister Shirley Muldon (Earl), brothers Jamey, Arthur (Patricia), Richard (Marlese), Roger (Josie), stepmother Barbara Jean, sister-in-law Teri Hepplewhite and many nieces, nephews and other relatives and friends around the world.

He was predeceased by his father Neil Benjamin and his mother, Alma Jean.

Born and raised in Hazelton, BC, Neil's love for the land and its people was evident through all stages and aspects of his life. His hereditary name was Madiigam Gyamk, from the Gitxsan House of Gitluudaahlxw.

Neil met his wife to be (Barbara Hepplewhite) at Gladstone Secondary, graduating in 1960. He attended UBC and eventually enrolled in the Mining Diploma program at BCIT, where he emerged from the first BCIT graduating class in 1966.

Life took him many places, living and working throughout BC, Yukon, Manitoba, Ireland, Arizona, Ottawa and eventually 150 Mile House. While these were all special to him, his home was always Hazelton and their beloved Temlaham Ranch on the banks of the Skeena River.

His early career included logging with his father and working in mining exploration during the summers while still attending school. He worked for Kennecott Exploration, Amax Exploration, 'Ksan Historical Village, the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council, Assembly of First Nations and with countless First Nations communities and organizations throughout BC and the Yukon.

Always working with and on behalf of his nation, he helped advance Aboriginal Rights and Title at the local, Provincial and National levels. Much of his work set the stage that launched the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case, Delgamuukw v. The Queen, where in 1987/88, he spent 34 days on the stand as an expert witness defending the knowledge of Gitxsan Elders and leaders.

He was also co-chair of the Federal-Provincial Constitutional round on Aboriginal Issues for the Charlottetown Accord and a mediator during the Oka Crisis.

In 1992 Neil established Sterritt Consulting, where until just recently, he utilized his vast experience to assist indigenous organizations with aboriginal and treaty rights, self-government and leadership skills development.

Neil participated on many governing bodies, including the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology, Royal BC Museum and Royal Canadian Geographical Society, as well as many commissions and committees worldwide. This included extensive work and speaking engagements in Australia, New Zealand, Norway, East Malaysia, Thailand and the United States.

He authored many articles, papers and books of which his pride was "Mapping My Way Home, A Gitxsan History." A culmination of years spent researching his Gitxsan and European roots. The book received the 2017 BC Book Prize Roderick Haig-Brown Award and second place in the 2017 BC Historical Federation for Historical Writing.

Considered by many to be an extraordinary man for his passion, humility and integrity, everything he did, he poured his heart into. He was extremely honoured and proud to be awarded the Queen Elizabeth Golden Jubilee Medal (2002), Honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from the University of Toronto (2008) and University of Victoria (2017) and the Order of British Columbia (2017).

While this is a short glimpse into his incredible life and accomplishments, of which his most significant was his family -- in Neil's words if you would like to know more, "...it's in the book."

In lieu of flowers or donations, we ask that you spend time with your loved ones, enjoy the outdoors or raise a glass of your finest and toast to lasting, lifelong friendships and beyond. This is what he would wish for you.

At a time when we can safely gather, a Celebration of Neil's life will be held in Hazelton BC.

Published on April 15, 2020

Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History

by Neil J. Sterritt

Smithers: Creekstone Press, 2016.

$29.95 / 9781928195023

Reviewed by Dorothy Kennedy

*

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council in the 1980s.

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council in the 1980s.From 1975 to 2009, Neil Sterritt and his family lived at Temlaham Ranch, the site of a Gitxsan ancestral village on the Skeena River (a.k.a. Temlaxam or Dimlahamid), during which time he was hired as land claims director for the Gitksan-Carrier Tribal Council. A member of the House of Gitluudaahlxw, he was president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years leading up to the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case known as Delgamuukw v. B.C.

Between 1984 and 1991 the case known as Delgamuukw v. British Columbia made its way through the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en people claimed title to over 58,000 square km of B.C.

Two Gitxsan chiefs held the hereditary name Delgamuukw during the court case: Albert Tait, who was Delgamuukw during the preparation of the trial, and Kispiox carver Earl Muldoe, who assumed the name in 1987 after Tait's death. On the Wet'suwet'en side the chief was Alfred Joseph, whose chiefly name was Dini ze' Gisday'wa.

In his judgment of March 1991, Chief Justice Allan McEachern dismissed the role of oral history and determined that Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en title was extinguished when B.C. joined Confederation. In his infamous judgement, McEachern opined that:

[caption id="attachment_34102" align="alignleft" width="250"]

Judge Allan McEachern, 1993. "Nasty, brutish and short."[/caption]

Judge Allan McEachern, 1993. "Nasty, brutish and short."[/caption]It would not be accurate to assume that even pre-contact existence in the territory was in the least bit idyllic. The plaintiffs' ancestors had no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles, slavery and starvation was not uncommon, wars with neighbouring peoples were common, and there is no doubt, to quote Hobbes, that aboriginal life in the territory was, at best, "nasty, brutish and short."

The Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en appealed appealed McEachern's ruling to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in 1997 that the B.C. government had no right to extinguish the Indigenous peoples' claim to their ancestral territories and that oral history was a legitimate type of evidence.

Reviewer Dorothy Kennedy concludes that, in Mapping My Way Home, Neil Sterritt "has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people's place and history in this province and this book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw."

In Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016), Sterritt traces the history of the area at the junction of the Skeena and Bulkley Rivers, the resiliency of the First Nations residents who have maintained the villages of Gitanmaax and Hazelton, as well as his own personal story of growing up in Hazelton and helping his people fight the Delgamuukw court case. His overview stretches from the creation tales of Wiigyet to the advent of oil and gas pipeline proposals, including tales of the Madiigam Ts'uwii Aks (supernatural grizzly of the waters), the founding of Gitanmaax, Kispiox and Hagwilget and the coming of the fur traders, miners, packers, missionaries and telegraphers.

Mapping My Way Home was awarded the 2017 Roderick Haig-Brown Region Prize for the best book to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia, an honour thoughtfully bestowed upon an author who has contributed greatly to the history of our province through contextualizing and elucidating his people's oral history that almost thirty years ago evaded Chief Justice McEachern's appreciation. - Ed.

*

The Delgamuukw v. British Columbia litigation in the Supreme Court of British Columbia provoked many responses and much scientific and legal discussion about the nature and reliability of oral history.

Among the most prominent anthropological and historical specialists reflecting on these questions was a collection of scientists whose criticism of the Court appeared in a special issue (Autumn 1992, vol. 95) of BC Studies, entitled Anthropology and History in the Courts. Guest Editor Bruce Miller concluded from these articles that the materials submitted to the Court by anthropologists and historians "were improperly utilized and badly understood."

Certainly, Chief Justice Allan McEachern's lengthy "Reasons for Judgement" of 1991 on this long and costly trial presented a large target for anthropologists whose rebuttal to his stinging dismissal of their discipline resulted in a mass outcry, along with some more solemn and private self-reflection. Subsequent court witnesses have both profited and suffered from the backlash, learning from the earlier Court's reaction that experts, when amassing and analyzing oral histories, need to apply the tools of their profession more transparently.

The Court told us that evidence used within the restrictions of the western legal and political system, where the people-land relationships have been misrecognized by law and by policy, also requires greater attention to the historical context of the information and the recognition of conflicting stories.

If, paradoxically, Delgamuukw served anthropology well in bringing about more critical self-reflection of its methods, it served the First Nations even better by necessitating the collection of oral histories dispersed among elders and archives into a coherent story that connected a people to its homeland.

For Neil Sterritt, a member of the Gitxsan and author of Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History, research undertaken in preparation for the litigation immersed him in an ancient world created at Temlaham, a place he knew as a child, left as a teenager to pursue schooling and an international career in geology, and returned to as an adult where he served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years in those communities' preparation for Delgamuukw.

Strategy developed for the trial preparation in a series of meetings with Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en elders between 1981 and 1984 led to the transfer of the chiefs' knowledge of their territories onto maps and the collation of supporting documentation. The materials discussed boundaries of Houses, confirmed specific place names, and recorded descriptions of landmarks and resource use that together would present the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en chiefs' views of their world.

Sterritt and a team of researchers spent eight years building upon earlier ethnographic studies, including Sterritt's own mapping project begun in 1975. As Sterritt explains, "Contrary to the strategy used in the Calder case [1973] where one expert witness [anthropologist Wilson Duff] was called to prove title, our strategy was to defeat the extinguishment argument and to prove Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en title by placing a substantial body of evidence from the elders about our land, laws and oral histories against the meagre evidence of the crown and its sovereignty assertions" (p. 310).

Delgamuukw is significant, for the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 unanimously decided that Aboriginal title consists of the right to exclusively use and occupy the land including the right to choose how the land can be used.

However, what the Gitxsan gained from the litigation was more than an impressive legal victory, for they created an archives and library that should continue to provide an enduring legacy of their people's history from the mythical time of Temlaham through to their people's role in Canada's recognition of landmark legal principles.

For Neil Sterritt, what emerged from his preparation for the litigation was a deeper comprehension of his homeland. In Mapping My Way Home, it is through Sterritt's integration of the many forms of evidence compiled for the trial that the people-land relationships of the Gitxsan become clearly apparent.

His skilful weaving together of his personal journey of discovery with the accounts of ancestors and elders, coupled with historical and resource-use maps, and with the histories of both the local settler and Indigenous communities along with that of his Newfoundland mother, provides a more familiar and accessible route towards understanding the Gitxsan-Wet'suwet'en and their territories than any of the documents alone.

With such a volume of materials to draw from, including numerous expert reports, Sterritt's book is at times dense; at 354 pages it is far-reaching. But Sterritt has selected and told his story well. He has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people's place and history in this province. This book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw.

*

Dorothy Kennedy is a consulting anthropologist, occasional university lecturer and expert witness specializing in the Indigenous cultures of British Columbia, Washington State and, most recently, Alberta and the Yukon. She completed a Doctorate from the University of Oxford in 2000, and an award-winning Master's degree from the University of Victoria, where she has taught in the Anthropology Department and the Indigenous Education Program. For the past four decades, including two decades devoted intensively to ethnographic and linguistic fieldwork in First Nations' communities, she has been engaged full-time in the research process, from conceptual planning and document review to issue-focused research, analysis, and reporting. She is the author or co-author (primarily with her colleague and husband, Randy Bouchard), of hundreds of reports, as well as numerous published articles and books, both scientific and popular, including four articles in the Plateau and Northwest Coast volumes of the Smithsonian Institution's Handbook of North American Indians and, most-recently, Talonbooks' The Lil'wat World of Charlie Mack (2010). Kennedy and Bouchard are also editors of the well-acclaimed Indian Myths and Legends from the North-Pacific Coast of America, a translation of Franz Boas's first and significant collection of B.C. First Nations' mythology published by Talonbooks in 2002, and originally published in German in 1895. As of 2018, she was with Bouchard & Kennedy Research Consultants at Mill Bay, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Reviewis a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

"Only connect." - E.M. Forster

Home

Home