John Borrows of the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation became the Law Foundation Chair in Aboriginal Justice at the University of Victoria Faculty of Law in 2001. As Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria classroom, John Borrows and fellow professor Val Napoleon co-founded a unique four-year law education program that confers an Indigenous law degree, touted as the world’s first. Students who graduate will qualify to practise both Canadian common law, or Juris Doctor, and Indigenous law, Juris Indigenarum Doctor. In November of 2018, there were 26 inaugural students.

Borrows was raised near the Cape Croker Indian Reserve on Georgian Bay, Ontario and his great-great-grandfather was signatory to a 1.5-million acre treaty with the Crown. Borrows attended University of Toronto, studying history and politics, before gaining a Ph.D. at Osgoode Hall Law School. Dubbed "Canada’s pre-eminent scholar of Indigenous and Aboriginal law” by Dalhousie University when he received an honorary doctorate there, Borrows, at 55, won the the Canada Council for the Arts’ Killam Prize in Social Sciences.

He is the author of Recovering Canada: The Resurgence of Indigenous Law (2002), for which he won the Donald Smiley Award for the best book in Canadian Political Science, as well as Aboriginal Law: Cases, Materials and Commentary (1998). Borrows was the first academic Director of First Nations Legal Studies at the University of British Columbia and he founded the Intensive Program in Lands, Resources and First Nations Governments at Osgoode Hall Law School. He has taught more than 400 Aboriginal law students and helped initiate the June Callwood Program in Aboriginal Law at the University of Toronto. He received a National Aboriginal Achievement Award in the category of Law and Justice in 2002.

Some early articles by Borrows prior to 2003:

"Because it Does Not Make Sense...": An Analysis of Delgamuukw v. The Queen", Osgoode Hall Law Journal

"Landed Citizenship: Narratives of Aboriginal Political Participation" Will Kymlicka, ed., Citizenship (Oxford University Press)

"The Supreme Court, Citizenship and the Canadian Community: Judgments of Justice G.V. La Forest", Wade MacLachlan et al. eds., Gérard V. La Forest at the Supreme Court of Canada, 1985-1997 (The Supreme Court of Canada Historical Society, 2000).

"Reliving the Present: Title, Treaties and the Trickster in British Columbia", (1998) B.C. Studies 99.

"Frozen Rights in Canada: Constitutional Interpretation and the Trickster", (1998) 22 American Indian Law Review 37.

"Living Between Water and Rocks: First Nations, the Environment and Democracy", (1997) 47(3) University of Toronto Law Journal 417.

"The Sui Generis Nature of Aboriginal Rights: Does it Make a Difference?", (1997) 35 University of Alberta Law Review (with Len Rotman).

"The Trickster: Integral to a Distinctive Culture", (1997) Constitutional Forum 29 - 38.

"Wampum at Niagara: First Nations Self-Government and the Royal Proclamation" Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada (UBC Press, 1999).

"Traditional Contemporary Equality: The Impact of the Charter on First Nations Politics", Charting the Consequences: The Impact of the Charter of Rights on Law and Politics in Canada (U. of T. Press, 1997).

"Incremental Planning and the Ontario Municipal Board", (1996) 10 Canadian Journal of Administrative Law and Practice.

"With or Without You: First Nations' Law (in Canada)", (1996) McGill Law Journal 630 - 665.

"Fish and Chips: Aboriginal Fishing and Gambling Rights in the Supreme Court of Canada", (1996) 50 Criminal Reports 230 - 244.

***

Voicing Identity: Cultural Appropriation and Indigenous Issues edited by John Borrows and Kent McNeil (UTP $36.95)

Excerpt (BCBW 2023)

Who is qualified to write about Indigenous culture? Turns out it can be as difficult an issue for Indigenous people as it is for non-Indigenous people.

UVic law prof John Borrows, a member of the Chippewa of the Nawash First Nation, and York University emeritus prof Kent McNeil gathered Indigenous and non-Indigenous people together to discuss the oftentimes thorny problems of Indigenous cultural appropriation for a workshop and then published some of their stories in Voicing Identity, a collection more personal in tone than legalistic.

To illustrate how appropriation can be leveled at Indigenous people, too, Borrows asks: “Does a Mohawk academic from Akwesasne have any more authority to research and teach about Haida traditions and law, one might ask, than a non-Indigenous academic who grew up on the West Coast? Does being Indigenous provide the Mohawk scholar with special insight into Haida culture and worldview that a non-Indigenous scholar can never acquire?”

Borrows cites a specific Canadian example that comes from the world of entertainment to illustrate how Indigenous people are not immune to accusations of cultural appropriation: “Cikwes (Connie LeGrande), a Cree songwriter and performer, utilizes Inuit throat singing in her music. When she received a nomination for a folk music award at the Indigenous Music Awards held in Winnipeg on 17 May 2019, a number of Inuit performers accused her of cultural appropriation and said they would boycott the awards ceremony as a result. One of the Inuit throat singers, who goes by the name Riit, explained: ‘Just because you’re part of another Indigenous group, it doesn’t give you the right to take traditions from other groups.’”

In her story for the book, Anishinaabe-Métis law prof Aimée Craft examines the line between support of Indigenous cultures and the exploitation of them. She surveys the Indigenous art and clothing she owns, wondering if she has the permission to display and wear these cultural items. As she does so, Craft notes that cultural appropriation is not limited to the taking of Indigenous things by non-Indigenous people. It depends on “how things are acquired, what they are used for, and whether proper respect has been paid and protocols followed.” Craft concludes an important element is “the building of relationships, mutual consent and reciprocity” and that she meets this criteria because all the art she has acquired is “rooted in my relationships.” That’s because Craft has deep personal connections to the creators of the art she hangs on her walls and the jewellery and clothing that she wears. Displaying the work of her friends “is a celebration, a resistance of sorts, against the Canadian colonial imperative of assimilation.”

To demonstrate how relationship building is critical for reconciliation, kQwa’st’not (Charlene George) and Hannah Askew, executive director of the Sierra Club BC, co-authored a story about how they have worked together for the past two years to facilitate a cross-cultural transformation of the environmental charity located on Lekwungen territory.

Part of the work involved painting a mural at a nearby middle school that invited voices and views about nature that have been notably absent in the environmental movement. Askew recalls an important learning moment, reprinted here:

“One week, while I happened to be away, kQwa’st’not dropped by the Sierra Club offices on a Friday afternoon with an enormous batch of cookie dough. She gathered together the staff who were in the office that afternoon and asked everyone who was able to take some home over the weekend to bake and bring it back in order to have them ready to share with all the children at the middle school who had helped with the painting of the mural. kQwa’st’not explained that because she only had one small oven in her home, it would be difficult for her to bake the many hundreds of cookies by herself. At the time, kQwa’st’not was new to the organization and few of the staff had had an opportunity to develop a relationship with her. The staff were quite surprised by her request. While a few agreed, most said that for different reasons they were unable to help. kQwa’st’not left most of the cookie dough in the fridge with an invitation for anyone who was able to help. She said that she would be back on Monday to pick up the baked cookies. On Monday, she returned and picked up the baked cookies from those who had been able to help, as well as the unbaked dough still sitting in the fridge. She then baked the remainder of the cookies herself, to share with the children at the school in celebration at the unveiling of the mural.

When I returned to the office the following week, a number of perturbed staff came to speak to me about the baking request, pointing out to me that baking cookies was not a part of their job description and explaining that they felt somewhat guilty not to have helped. They were also surprised and uncomfortable to have been asked, since it was out of the ordinary. Since I had not spoken with kQwa’st’not about the cookies, I was not sure what had happened but promised to speak with her and find out more. When we talked, kQwa’st’not explained to me that she had wanted to share a teaching with the staff which would simultaneously invite them into Coast Salish protocol of providing food for guests (the children) at a gathering, as well as help them to reimagine their relationships with her and other staff members in a more intimate and familial way. This teaching would materialize as people pitched in and helped one another in ways that were not in their specific job descriptions and work hours. They would learn as they engaged in a more holistic way outside of their formal roles. The invitation was completely optional. If they chose to participate, it offered an opportunity to staff to experience their roles and relationships to one another and herself in a different way. kQwa’st’not did not directly explain this to the staff — they came to this understanding over time by learning other stories and teachings that kQwa’st’not shared. Many of the staff eventually began to affectionately refer to the incident as “the cookie test.” 9781487544683

***

BC contributors to Voicing Identity also include: Sarah Morales (Su-taxwiye), who is Coast Salish and a member of Cowichan Tribes. She is an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at UVic, where she teaches torts, transsystemic torts, Coast Salish Law and languages, legal research and writing, and field schools.

UVic prof Michael Asch, has written and edited a number of books, including Home and Native Land: Aboriginal Rights and the Constitution (1984), Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equality and Respect for Difference (1997), and On Being Here to Stay: Treaties and Aboriginal Rights in Canada (2014).

Keith Thor Carlson was hired by the Stó:lō Tribal Council to be their staff historian in 1992 and has been working with Coast Salish Knowledge Keepers ever since. Currently a Prof of History at the University of the Fraser Valley, Carlson was made an honorary member of the Stó:lō Nation in 2001.

UVic Professor Emeritus Hamar Foster is a settler. He and his partner have two grandchildren who are members of the Heiltsuk First Nation. He is a coeditor of To Share, Not Surrender: Indigenous and Settler Visions of Treaty-Making in the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia (UBC Press, 2021).

BOOKS:

Aboriginal Law: Cases, Materials and Commentary (1998)

Recovering Canada: The Resurgence of Indigenous Law (2002)

Aboriginal Law: Cases, Materials and Commentary (Butterworths, 1998, 2003)

Drawing Out Law: A Spirit’s Guide (2010)

The Resurgence of Indigenous Law (University of Toronto Press, 2002)

The Right Relationship: Re-imagining the Implementation of Historical Treaties (U of Toronto Press 2017) Edited by John Burrows and Michael Coyle $85 978-1-4426-3021-5

Canada’s Indigenous Constitution

Editor. Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings (U of T Press, 2018) $32.95 978-1-4875-2327-5. Co-editors Michael Asch and James Tully.

Law's Indigenous Ethics (U of T, 2019) $39.95 978-1-4875-2355-8

[BCBW 2019] ILMBC2

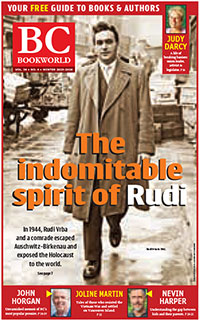

[caption id="attachment_21002" align="alignleft" width="275"]

Borrows receives Killam Prize[/caption]

Borrows receives Killam Prize[/caption]e Canada Council for the Arts’ Killam Prize in Social Sciences.

Home

Home